Westminster Abbey

For this Coronation Special episode, we’re going to be discovering the history and life of what is arguably the architectural protagonist of King Charles III’s coronation ceremony.

While everyone’s watching the guy with the Crown on his head, the destination historians will be looking up in wonder at the amazing space being used.

Building the Abbey

Westminster Abbey these days acts as your normal church, offering daily services for anyone who would like to wander on in. It just so happens to also be a World Heritage Site with over a thousand years of history behind it.

The Abbey has seen everything from coronations, to royal weddings, to funerals. It has seen many of Britain’s most significant historic moments and yet still stands to, no doubt, see many many more.

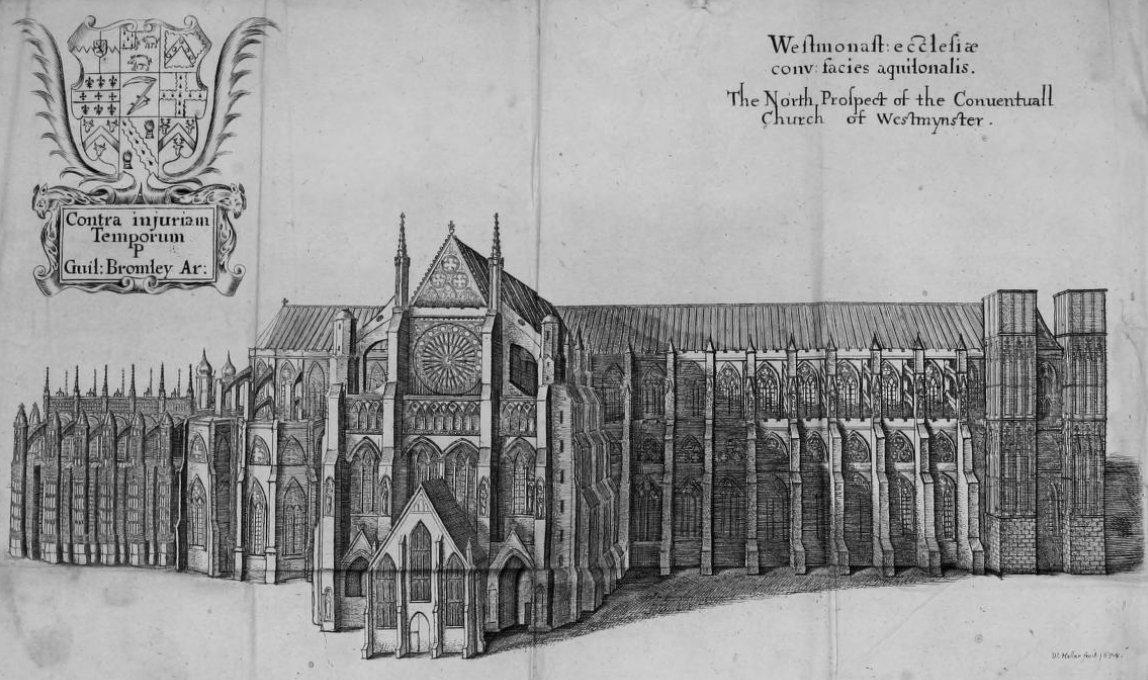

Sitting just west of the Houses of Parliament in the Greater London Borough of Westminster, the Abbey is nothing short of an architectural masterpiece.

So how did Westminster Abbey get started? For that we’ll have to head on all the way back to the first Christian King of the East Saxons. He reportedly founded a small church on a small island in the River Thames, which at the time went by Thorney Island.

We know that by 785 AD, there was a small group of monks that called the island home, and around 960 AD the monastery was enlarged and remodelled by St Dunstan of Canterbury.

It would be on Thorney Island, near this monastery, that King Edward, later St Edward the Confessor, established his royal palace in the 1040s. Edward chose to greatly enlarge the monastery, building a big stone church to honour St Peter the Apostle. It was this church that started to be known as ‘west minster’, in order to distinguish it from the east minster, otherwise known as St Paul’s Cathedral, over in the City of London.

Unfortunately Edward’s monastery and church hasn’t really survived all that well. The only traces that remain of it today are in round arches and huge supporting columns of the undercroft and the Pyx Chamber in the cloisters, its actually the undercroft that was the original domestic quarters of the monks. I’ve included a photo of the floor layout in the image section of this website, if you would like to get a feel for the spaces within the Abbey.

It was on Christmas Day 1066, that William the Conqueror was crowned as King of England. He would then move Edward’s body, which had until now been entombed in the High Altar, to a new tomb a couple of years after his canonisation which happened in 1161. This shrine to Edward survives today and you can see medieval kings and their consorts buried around it.

In fact the Abbey has been the coronation church for every coronation ceremony since 1066, and is the final resting place for 17 monarchs and over 3000 British greats.

The original Abbey that Edward set up was around for about two centuries until Henry III decided to rebuild it in the new Gothic style that was all the rage in the middle of the 13th century. And so it is largely Henry III’s church that we see when we look at Westminster Abbey today.

Henry loved St Edward the Confessor and was so devoted to him that he wanted to build a more significant church to the Saint, whilst also providing a new shrine where he could be put at rest, which happened to be near to where Henry himself would be buried.

In building the Abbey, Henry was able to create a large space or ‘theatre’, under the lantern, between the quire and high altar, specifically putting aside space for the many coronations that were to follow, including the most recent coronation of Charles III.

Early on in Henry’s reign, we’re talking 1220 here, he had the stone foundation for a new Lady Chapel laid at the east end of Edward’s original church, but money got a bit tight at the time and no other work was carried out. That was until 1245, when Henry decided to pull down almost the entirety of Edward’s church. The only parts of Edward’s original church that remained was the nave, the cloisters, the Pyx Chamber and the Undercroft.

For a couple centuries, Westminster Abbey plodded along avoiding any real damage or great change. It even managed to avoid the dissolution of the medieval monasteries in January 1540. Thanks to its connections to royalty, mainly due to all those coronations, weddings, funerals and internments over the years, Henry VIII spared the Abbey during the Reformation. And it was this same year that Henry VIII officially named Westminster as a cathedral with its own bishop, dean and 12 prebendaries, which today we call canons. Although about a decade later in 1550, the bishopric was surrendered and Westminster was made, by an Act of Parliament, a cathedral church in the diocese of London.

And so it fell to Mary I to restore the Benedictine Monastery in 1556 as she went about restoring Catholicism in England. Although it didn’t last too long, as the Abbot and monks would once again be removed in 1559 when Elizabeth I came to the throne.

It was also Elizabeth I who founded the Abbey as the Collegiate Church of St Peter Westminster, which is the formal name of the Abbey, in 1560. The Abbey is neither a cathedral nor a parish church, it is actually a ‘Royal Peculiar’, which means it’s a church with an attached chapter of canons, and is headed by a Dean, but is answerable only to the Sovereign, not to any archbishop.

And because of this Royal Peculiar status, the Dean and Chapter were largely responsible for the civil government of Westminster, something they didn’t fully give up until the early 20th century. And it’s in this way that the Abbey has shaped a large part of English life, not to mention being at the centre on days of national importance.

The Abbey’s architecture

The architecture of Westminster Abbey is pretty astonishing to admire. It’s even considered to be one of the most important Gothic buildings in the country, and it doesn’t hurt that its original shrine is medieval.

But we have to remember that the architecture we’re looking at here isn’t medieval, nor is it original. It’s Henry III’s architecture that we’re looking at, and we can definitely see where he got his ideas from. There’s clearly a major influence from the cathedrals that were being completed over in France. It’s all there, especially when you look at the rose windows, the ribbed vaulting, the pointed arches and we can’t forget about those flying buttresses.

The interior of the Abbey has the highest vault or ceiling in England, measuring in at almost 31 metres, and the narrow single aisles only make it seem all the taller.

The last section of the Abbey to be completed was the West Towers in 1745. The construction of these had originally started way back in the medieval times but had remained unfinished. So it was up to Nicholas Hawksmoor to finish them off several centuries later in Portland Stone. Interestingly you might often hear that the towers were designed by the famed architect Sir Christopher Wren, but it was actually Nicholas Hawksmoor and John James who sorted the project out.

Speaking of Portland Stone, the exterior of the Abbey has been refaced several times over the centuries, each time in a different type of stone. Like we saw with the facing of Buckingham Palace, weathering and pollution from the Industrial Revolution did their damage.

And it’s not just the exterior that has had serious restoration work done. Parts of the Lady Chapel have been restored mainly in the 1800s, several statue niches have needed some help, not to mention the statues themselves, and in the mid-19th century a large part of the Chapter House.

If you were to pop round to the Abbey’s Great West Door and look up, you would see ten statues representing modern martyrs. These martyrs represent everyone who has been oppressed or persecuted for their faith. Among the statues you can see a nod to the victims of Nazism, communism and general religious prejudice, all having taken place in the 20th century.

It was in the 15th century, that these niches were built, but for whatever reason they were never filled with statues. So when a major restoration of the west front was completed in 1995, it was decided to place some statues in these empty niches. But the Abbey didn’t want to just put your stock standard saints in there, that’s been done hundreds of times before, they wanted something a bit different, and so they came up with the idea of 20th century Christian martyrs.

And so a committee, headed by the Sub Dean of the Abbey, sat down and came up with a list of individual martyrs that could stand above the Great West Door and represent all those who have been oppressed or persecuted. So next time you wander by that side of the abbey, you can admire everything they stand for.

Because Westminster Abbey was built during the medieval ages, you would also expect the windows to have been made and installed in the medieval period, and they were, but time has not been kind to the Abbey’s glass, and there is very little of it that remains.

Some 13th century panels were managed to be preserved, but the great west window and the rose window that lives in the north transept are from the 18th century, and the rest of the glass is even newer dating from the 19th century to the 21st century.

Although thousands of fragments of stained glass believed to be from the 13th to 16thcenturies were found during work to install the new Galleries, and these small pieces have been added to some of the new windows, so that’s a pretty great use of recycling.

So we can really see that time has not been kind to the Abbey’s windows, almost all the original Tudor glass has been lost from Henry VII’s Lady Chapel, the most recent being lost thanks to the blasts curtesy of the Second World War, but I guess that’s the risk that comes with being in the centre of a European city.

Luckily in some parts of the Abbey, such as the east cloister windows and the Chapter House, the bits of glass that were able to be salvaged after the war have been reused in newer windows, so just because it’s not in its original state doesn’t mean it can’t be useful.

But there is some glass that is still original. The oldest glass in the Abbey can be found in the east window of St Margaret’s Church. You can see it above the altar displaying a depiction of the crucifixion. This window was created to commemorate the marriage of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, and it’s this window that got removed and was safely hidden away during both world wars.

The Abbey’s interior

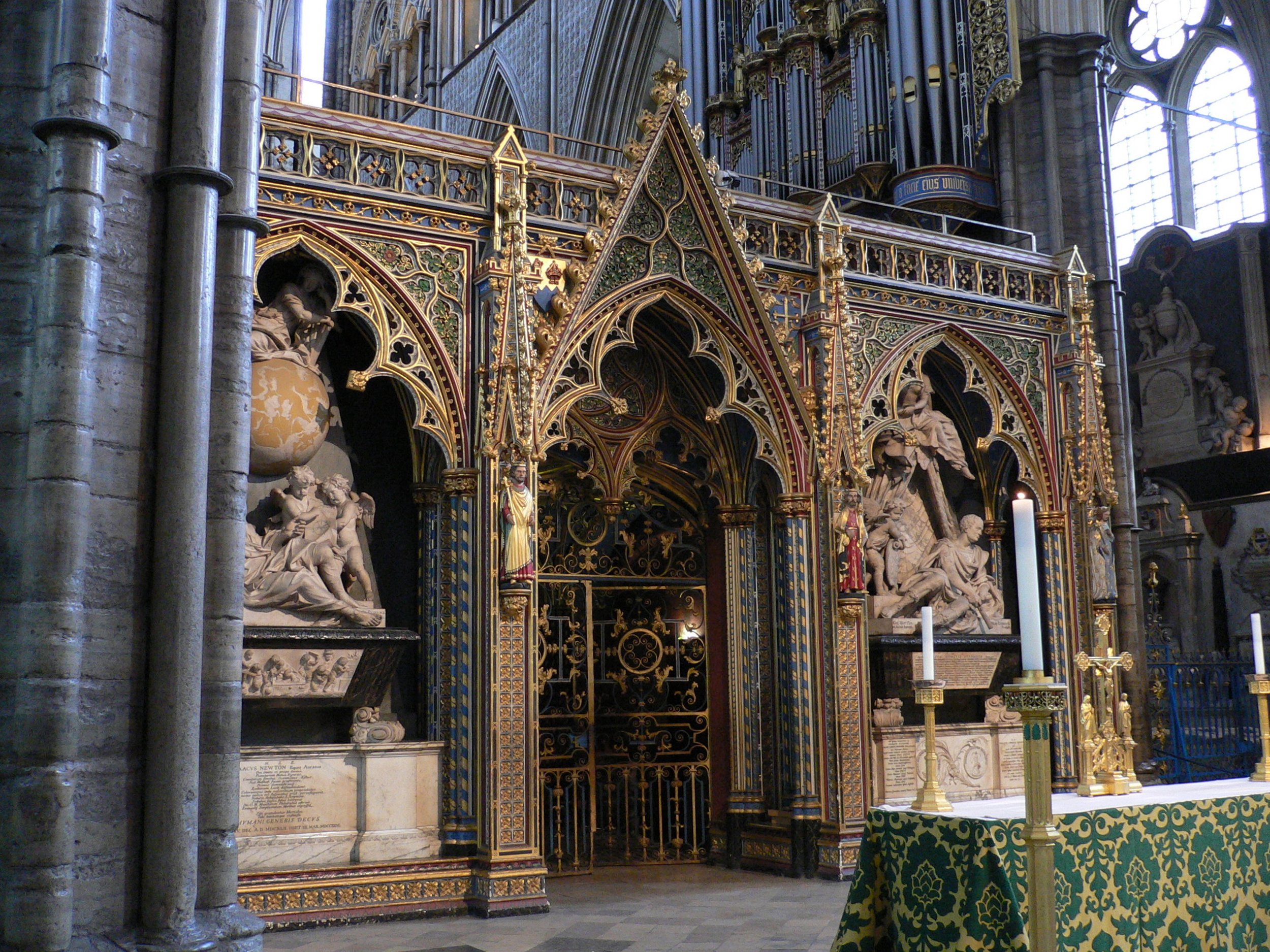

Probably the part of the Abbey we’re most familiar with at the moment is the area between the high altar and the quire, the spot where coronations take place.

But this magnificent part of the Abbey is nothing compared to the Lady Chapel, built by Henry VII in the 16th century, and is therefore commonly known as Henry VII’s Chapel. Also this kind of Lady Chapel is actually pretty common in most cathedrals and even large churches, as it’s a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. But it’s what Henry VII did with his Lady Chapel that has made it stunningly beautiful.

This Chapel has been called

…one of the most perfect buildings ever erected in England … the wonder of the world…

And it certainly is something to see. It’s a brilliant example of late medieval architecture, especially with its fan-vaulted ceiling. And to Henry, there was no expense too large for his chapel, which includes intricate carvings on the ceiling and hanging pendants.

All around you can see the Tudor rose and 95 statues of saints in the wall niches. There are even carved misericords on the stall seats. Even Henry’s own tomb is lavish in appearance, there are gilt bronze effigies of himself and his wife, Elizabeth of York, which can be seen at the east end of the chapel.

It's also here, every four years since 1725, that the Sovereign has installed the new Knights of the Order of the Bath, you’ll know you’re in the right spot because of their colourful heraldic banners.

The Pyx Chamber is actually one of the oldest parts of Westminster Abbey, having been built around 1070, that still survives. It’s got quite a low ceiling and is just off the East Cloister, and is part of the Undercroft, which we already know used to be a part of the monk’s dormitory. But in the 12th century, the Chamber was walled off, and then in the 13th century used as a treasury. Now this place is really a walk back in time, the two heavy oak doors date from the early 14th century, while the tiled floor appears to be original medieval with some tiles thought to date back to the 11th century.

But this name ‘Pyx’ is pretty interesting. Where did that come from? Well it came from the wooden boxes which held gold and silver pieces that were waiting for their turn in the ‘Trail of Pyx’, which is where they melt down the coin pieces to prove that the coins are worth their currency. This was done mainly because back in the day, this ‘Trial’ was reportedly established all the way back in 1281, people would cut bits off the coins, or melt the coins down and then recast them by mixing them with other lesser metals, effectively creating counterfeit coins. People were very thrifty like that back when coins were made out of real gold and silver. The whole Trial process still happens today, but no longer in the Pyx Chamber, these days it takes place in the Goldsmiths’ Hall in the City of London.

Let’s now turn our attention to something that every church has, music. Music has been a part of Westminster Abbey for thousands of years. The choir that sings the daily choral services at the abbey, do so from the stalls in the quire, spelt with a ‘q’, but pronounced the same. This daily singing is supposedly a tradition that started with the plainsong chanting by the monks back in the 10th century.

The other stalls in the quire have been assigned to members of the clergy and officers of the Abbey. And as the years have gone by High Commissioners for Commonwealth countries have been assigned one of these seats when attending a service, such as was done for the Queen’s funeral in September 2022, and has been done for the Kings coronation in May 2023. Unfortunately the quire stalls that stand today, are not original, the medieval quire stalls that were originally installed were replaced in the 18th century, and then again the present ones were put in 1848. So while not quite medieval, the current stalls have certainly seen a thing or two. And the floor, those black and white marble tiles have been around since 1677, and no doubt had many a foot trample upon them.

Speaking of seeing a thing or two, the cloisters have certainly seen their fair share, especially since this was one of the parts of the Abbey where the Monks liked to hang out and so was one of the busiest. Although unfortunately 1298 saw a fire damage a majority of the architecture and so, like much of the Abbey itself, they aren’t entirely original. Although what we do see dates mostly from the 13th to the 15th centuries. It’s actually in the cloister garth, where you will find a memorial fountain commemorating Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, we’ve came across his creative landscapes before, in our episode on Highclere Castle. But it’s not just this memorial that the cloisters contain, you can also find the graves of several Abbots of the original church, and some clergymen and church officials thrown in there as well.

The Chapter House is another part of the Abbey that has been the centre of a few things while it’s been standing. You can find it in the East Cloister and it was originally a meeting place for the monks and the abbot. With room for 80 monks on tiered seating and a central pillar holding the vaulted ceiling up, they would come together in this space to pray, read together and discuss what they had going on that day. It’s also here in the Chapter House that the King’s Great Council would meet in 1257. History would tell us that this would turn into the English Parliament, and it was actually also here that the House of Commons met for a couple of years in the 14th century.

While the Chapter House has stood since the early days of the Abbey, time has yet again not been kind, and it is to the Abbey’s Surveyor, a Sir George Gilbert Scott we must thank for rescuing and restoring the Chapter House in the mid to late 1800s, he even had the windows reglazed. Unfortunately like much of the rest of the Abbey these windows were damaged during the Second World War and what could be saved was re-used where it was needed. It’s also in the entrance to the Chapter House that you can see what is claimed to be the oldest door in Britain, now I’m not sure how they go about proving that against all the other doors in Britain, but this particular one is believed to have been serving as a door since the 1050s. Now that’s a long time in the same job.

Contents of the Abbey

We know now that Westminster Abbey has been around for a good chunk of time and has been the centre of some pretty major life events. And it holds a fair amount of interesting stuff, I mean the place could easily be a museum if it wasn’t a working church. Gerlinde, the Abbey Marshal lays it out for us:

You are surrounded by history at the Abbey, not like a museum where it’s just displayed, but here you are standing where history has happened.

Let’s now discover just what are those interesting things the Abbey holds, and what better place to start than the Library.

The Abbey’s library, like most libraries out there I imagine, has an extensive collection of historic books, manuscripts, photographs, archival material and heaps of other things that finds its way into an Abbey library. It’s actually this very library that you need to go to if you wish to do any sort of research on the Abbey itself, because it is the only library that contains the extensive and historic collections of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster. So we’re talking about books and manuscripts dating from the 16th century here, some of the archives even go so far back as to the 10th century, when the Abbey was nothing but a small monastery. Now that’s some dusty old books. And the Abbey is not above reusing old spaces, the space that holds the library today used to be a part of the monk’s dormitories.

Now the library’s collection really grew in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially after the Dean, at the time of 1623, installed a couple of book presses to keep churning them out. And then another Dean left all his own personal books to the abbey library in 1774. The library now contains about 14 000 books that are believed to have been printed prior to 1801, there’s also a couple of medieval manuscripts in there, and a collection of music as well.

If you, yourself, wanted to carry out some of your own research in the library, you do need to make an appointment as the library has limited times that researchers can visit, mainly only between Tuesday and Thursday. And it’s not all that easy to get an appointment either. Because the seating is so limited, students need a letter of introduction from their supervisor, and much like the library at the Vatican, you can’t take photos and there’s no online catalogue for you to browse. Although if you are unable to attend the library in person, they are happy to get a digital or photocopy of the document you’ve requested, but this may take a bit of wrangling.

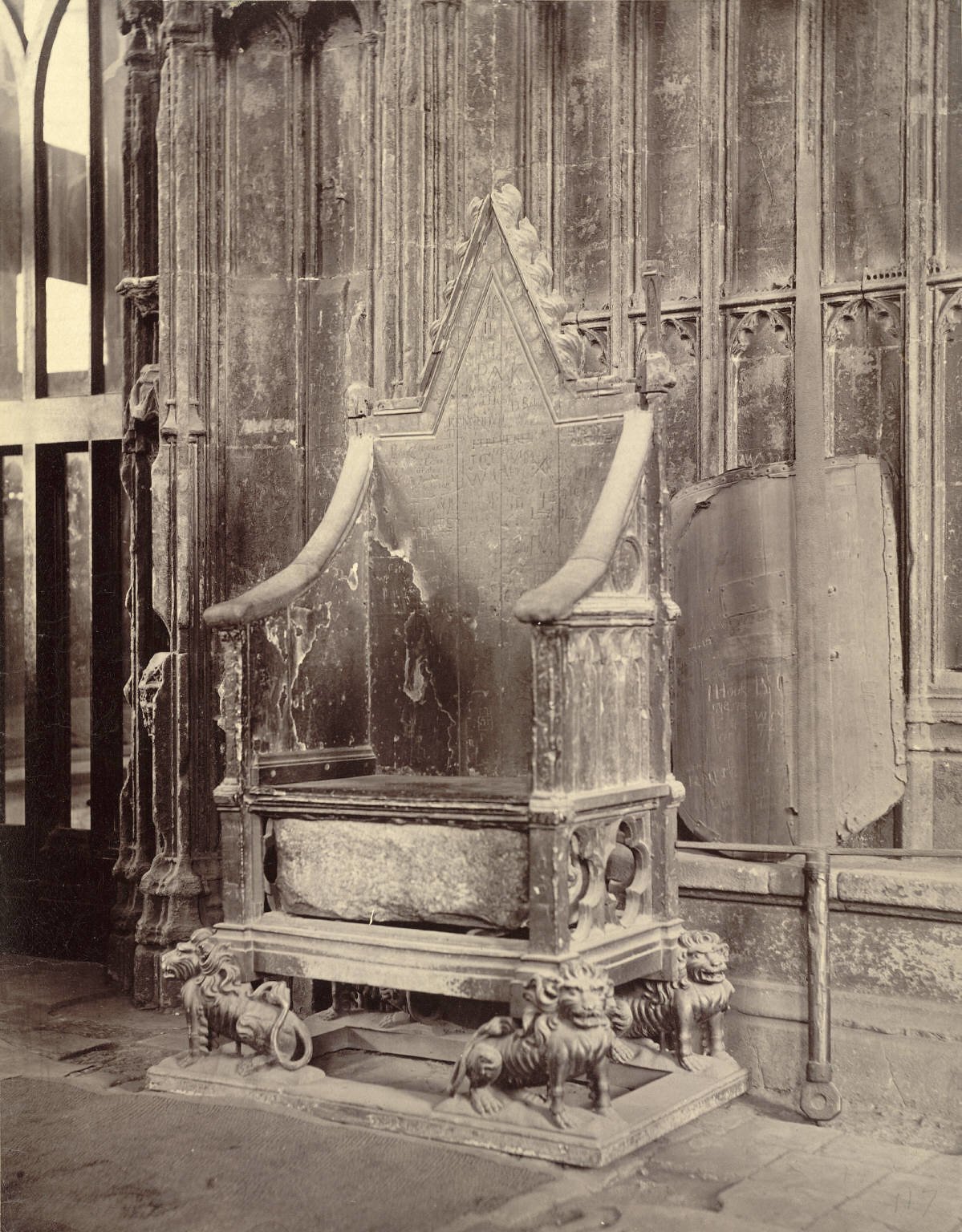

Probably the most recently exciting part about the Abbey is the Coronation Chair, and yes this is on display at the Abbey. There is an I Digress episode on this particular Chair and the Stone of Destiny that sits inside it, so if you would like to learn more about it then check out that Digression.

The Abbey is not only packed with things, but also with people, and not just the tourists. There are more than 3300 people buried within the abbey and even more who have been commemorated in some way. They include Kings and Queens, naturally, writers, scientists, noblemen and women, musicians and politicians. Good grief, surely by now it must be standing room only.

When you wander around the Abbey you might see commemorations to Jane Austen, Sir Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, William Blake, Martin Luther King, Jr, just to name a tiny few.

But it’s Henry VII’s Lady Chapel where you really hit the jackpot, with the Chapel being the burial place for 15 Kings and Queens. It’s here that you’ll see Elizabeth I, Mary I, Mary, Queen of Scots, and possibly the remains of Edward V and Richard, the Duke of York, who are otherwise known as the ‘Princes in the Tower’. Below ground there’s also the Hanoverian vault, containing the likes of George II and his family, as well as the Stuart vault where Charles II, William III and his wife, Mary II, and Queen Anne lie.

If you’re a literature lover, you will love the Poet’s Corner. You can find this ‘corner’, it’s not really a corner, on the eastern side of the south transept. Although because Britain likes to pump out pretty remarkable authors, they have sort of seeped out of their corner and into the rest of the Abbey. There are actually more than 100 burials or memorials in the Poet’s Corner. It’s in this space that you’ll see Shakespeare, the Brontë Sisters, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen. It was actually Geoffrey Chaucer, the author of The Canterbury Tales, who was the first poet to be buried in this space. And about 200 years after his death a writer for Elizabeth I who went by Edmund Spenser, asked to be buried near Chaucer, beginning a tradition of notable authors to be given the honour of having a memorial in Westminster Abbey.

But I think the most important burial at the Abbey is that of the Unknown Warrior. It was Army Chaplain, Reverend David Railton, who had served in France during the First World War who wrote to the Dean of Westminster in August 1920 with a suggestion of burying the body of an ‘unknown comrade’ in Westminster Abbey. The idea behind it was to give grieving families a place to remember loved ones whose remains were never returned from the war.

And so it was that plans were made for the burial of an ‘Unknown Warrior’ to take place in Westminster Abbey on Armistice Day, 11th November 1920, after the official end of the First World War.

Special precautions were taken to ensure that the identity of the chosen body was not known.

He might be a solider, sailor, or airmen and might equally be from the forces of the UK, the Dominions, or one of the British colonial territories.

Travelling from France with a full military guard, the coffin of the Unknown Soldier was brought up the Mall, via Admiralty Arch, and into Westminster Abbey, where the mourners were largely widows and mothers, even members of Parliament gave up their seats so that these people, deemed to have the greatest need for mourning, could attend.

The next week, the grave was filled with earth brought straight from France and an inscribed gravestone was laid, although it was replaced the next year by the black marble gravestone you can see today.

This idea of the burial of an Unknown Warrior really caught on, and several other nations have done something quite similar. But what’s unique about the British Unknown Warrior is that they were buried in a place of prayer. Here’s a small part of what’s inscribed on the tombstone.

They buried him among the Kings because he had done good toward God and toward his house.

The Abbey at war

The Abbey has seen its fair share of Wars, but it’s our most recent major war, the Second World War, that saw the most damage to the Abbey.

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, things moved fairly quickly, and as many of the Abbey’s treasures as was possible was evacuated out to country homes for safe keeping. These items included altarpieces from the 13th century, tapestries, tomb effigies, manuscripts and statues. 60 000 sandbags were even employed to protect some of the royal and medieval tombs that could not be moved. Some of the wax funeral effigies were even stored in the Piccadilly tube station, they were really putting things anywhere that they thought would keep them in one piece.

As the air raids became more frequent, the crypts were employed as shelter by the Abbey Staff. But the worst air raid to hit the Abbey was on the night of the 10th May 1941. Fire bombs fell to the Abbey floor, catching alight everything they could. Thankfully fire volunteers were on stand by to put any fire out as quickly as possible. But the ones that landed on the lantern roof weren’t able to be put out quickly enough, and it burned a hole through the lead roof. With flames reportedly 12 metres high, there was fear for the area below, which just happened to be the space reserved for coronations and the medieval tiled floor. Luckily though the fire was able to be put out before it did too much damage.

While the Abbey survived with surprisingly little damage considering the event, it’s surrounds unfortunately suffered far more, with whole buildings being destroyed.

Since the war however, the Abbey has become a place to gather on important memorial days, such as VE Day, or Victory in Europe Day.

Royals and the Abbey

As we’re already aware, the British monarchy has quite the affiliation with Westminster Abbey. 30 of them have been buried within the Abbey, including Edward the Confessor, he was the first, Henry III, Mary, Queen of Scots, Queen Anne, Edward I, Eleanor of Castille, Edward III, Richard II and Henry V, even James I is buried in the Abbey. Elizabeth I is actually buried with her half-sister, Mary I, in quite a beautiful tomb.

Some royals are buried in the Abbey, but have no monument erected in their name because of a lack of space, like Charles II, Queen Anne, and Mary II and her husband, William III.

It was George II who was the last monarch to be buried in Westminster Abbey, the main reason probably being the lack of room, monarchs have since been buried at Windsor Castle, as we saw with the late Queen’s burial.

But it’s not all doom and gloom at the Abbey, 16 royal weddings have also been held at the Abbey, the most recent being that of Prince William and Catherine Middleton, the current Prince and Princess of Wales.

Although some of the other royals to have been married in holy matrimony at the Abbey include, Henry I and Princess Matilda of Scotland all the way back in 1100, there was Richard II and Anne of Bohemia in 1382, George VI and Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in 1923, and of course, Elizabeth II and Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten in 1947.

And then of course some of the lesser royals to have been married in the Abbey are Princess Margaret, Princess Alexandra, The Princess Royal, and the Duke of York.

Something pretty exciting about William and Kate’s wedding in 2011, was that while the Abbey was chook full with 2200 guests, nearly a billion more tuned in to the live coverage around the world.

And of course we can’t forget about the coronations that have taken place since 1066. There have now been 40 coronation ceremonies for reigning monarchs to have been held at Westminster Abbey.

The first one is believed to have been William the Conqueror in 1066, and almost all since. Before William’s coronation it seemed that there was no fixed location for the coronation ceremony, just wherever looked good on the day I guess. Although the first monarch to be coronated after Henry III’s rebuilding of the Abbey was Edward I in 1274.

An interesting coronation was the joint coronation in 1690 of William III and Mary II. While William used the traditional Coronation Chair, a special chair was made for Mary. There’s also been William IV, Queen Victoria, Queen Anne, Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II who have all been crowned at the Abbey.

The only monarchs believed to not have been crowned are believed to have been Edward V, who tragically ‘disappeared’ before his ceremony and is believed to be one of the ‘Princes in the Tower’, and Edward VIII, who abdicated before his coronation ceremony in favour of marrying the divorcee, Wallis Simpson. Which I’m told was quite the scandal at the time.

While Queen Victoria’s coronation renewed the religious aspects of the ceremony, it was Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation on the 2nd June 1953, that was televised for the first time around the world. And following her death, Buckingham Palace announced that King Charles’ coronation ceremony would be held on 6th May 2023, which we have only just witnessed, with Camilla, the Queen Consort, being crowned alongside him.

Here's a statement from Buckingham Palace suggesting things for this coronation may be slightly different than for one’s in the past:

The Coronation will reflect the monarch’s role today and look towards the future, while being rooted in longstanding traditions and pageantry.

As the coronation ceremony hasn’t yet taken place at the time of recording, here’s a little run down of what we can expect on the day.

The arrangement for the ceremony itself are all made by the Earl Marshall and his Coronation Committee. But it’s the Dean of Westminster who instructs the monarch on everything to do with the service. And it’s the Archbishop of Canterbury who is the one to physically place the crown on the monarch’s head.

The order of the day is largely unchanged since the coronations of the late 14th century. Luckily it’s all laid out in the medieval illuminated Latin manuscript, the Liber Regalis, otherwise I imagine those organising the whole thing would have a hard time remembering what they did for the last one, seeing as it was so long ago. Check out our digression episode on this coronation instruction manual if you want to know more about what actually happens in the coronation itself.

So next time you find yourself leisurely wandering through Westminster Abbey, think about all the monarchs that walked its stone and marble floors, as well as those resting forever underneath your feet.

-

Why are coronations held at Westminster Abbey? - Royal Central

My dad wouldn’t want Stone of Destiny at Coronation - BBC News

Coronation Music at Westminster Abbey - Royal.UK

Order of Service - Westminster Abbey

Queens Consort of Westminster Abbey - Westminster Abbey

Coronation Chair prepared for historic role - Westminster Abbey

-

Welcome to Westminster Abbey - Westminster Abbey

About Westminster Abbey - Westminster Abbey

Architecture - Westminster Abbey

Abbey in Wartime - Westminster Abbey

The Wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton - Westminster Abbey

Buried among the kings - Westminster Abbey

Famous people/organisations - Westminster Abbey

The Coronation Chair - Westminster Abbey

The Queen Elizabeth II window - Westminster Abbey

Stained Glass - Westminster Abbey

Lady Chapel - Westminster Abbey

Poet’s Corner - Westminster Abbey

Pyx Chamber - Westminster Abbey

Royal tombs - Westminster Abbey

The Cloisters - Westminster Abbey

Chapter House - Westminster Abbey

Modern Martyrs - Westminster Abbey

Royal Weddings - Westminster Abbey

The Abbey and the Royal Family - Westminster Abbey

Library & research - Westminster Abbey

The King: coronation date set - Westminster Abbey

A history of coronations - Westminster Abbey

Edwardtide - Westminster Abbey

History of Westminster Abbey - Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey - Britannica

Westminster Abbey - Historic UK

Disclosure: As an affiliate marketer, we may receive a commission on products that you purchase through clicking on links within this website.