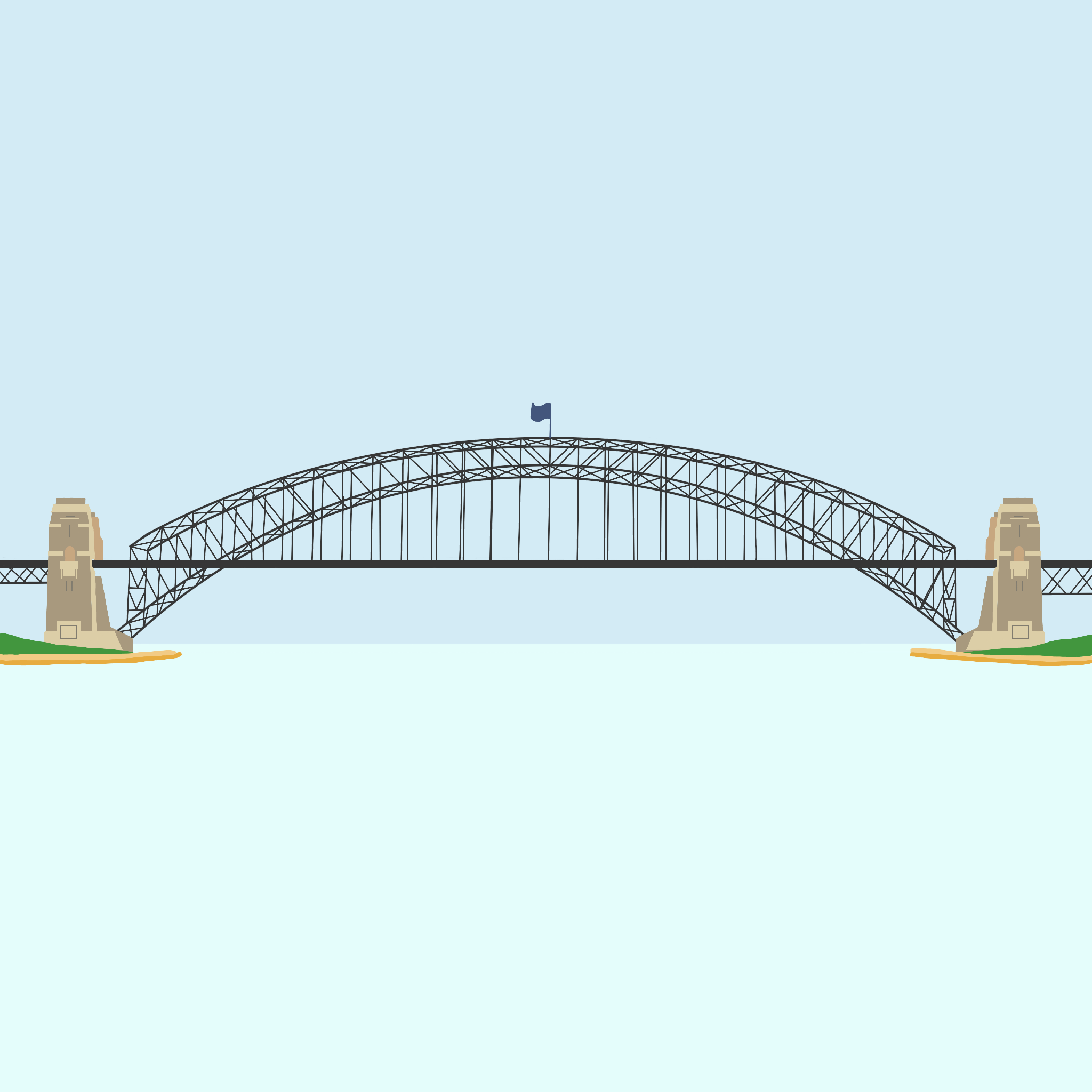

Sydney Harbour Bridge

A bridge that spans Sydney Harbour and stands as an Aussie icon

An Australian icon and spans the natural harbour of Sydney, the Sydney Harbour Bridge can be found on the National Heritage List and even has its own nickname: ‘the coathanger’. With the capacity for people to walk, cycle, drive or ride the train across it, the largest steel arch bridge in the world sees an average of 150 000 vehicles crossing it each day.

Before the bridge

The land that houses the bridge today was originally home to the Eora people of Indigenous Australia. Before the bridge, but after the colonisation of Australia, ferries were the only way to get across and around the harbour, otherwise you would be looking at a 20 km road route around the harbour which meant crossing five smaller bridges, this was super slow back then because travel was mainly by horse and carriage. There were two ferries that moved horse-drawn carriages and then later motor cars. And during the height of the ferry revolution, Milsons Point, a harbour-side suburb where today you can find Luna Park and the start or end of the bridge depending on which direction your moving, used to operate as the ferry-train-tram interchange for the North Shore of Sydney

In 1904, ferries carried 19 million passengers each year, meanwhile 131 million were carried by tram and 30 million by train. The ferries peaked in 1927 with 47 million passengers annually, the ferries were unable to cope with the increasing traffic, and thankfully the numbers fell to 20 million after the bridge opened. Now, you might be thinking 131 million people in 1904, sure!, but don’t forget for the average person, their trip would be twice a day, to get to where they were going and to get home.

Proposals for a bridge across the harbour had been suggested since the earliest days of the Colony. Attempts were made in 1900, 1903, 1911 and 1916, but due to political issues and pesky world wars, things were continually put on hold. But the earliest recorded drawing for a bridge was by engineer Peter Henderson in 1857. In January 1900, the government called for competitive designs and tenders for a bridge and by September 30 designs had been received and were exhibited in the Queen Victoria Markets in Sydney, which is known today as the Queen Victoria Building. John Bradfield, the Chief engineer for NSW Public Works, started planning for a bridge as early as 1912. He, himself, submitted several proposals for a bridge and in 1913, the parliamentary committee responsible for recommending a bridge chose Bradfield’s cantilever bridge design, but with the outbreak of WWI in 1914, the design did not go ahead.

With the ending of the war, 1921 saw the second round of tenders called for the construction of a bridge across the harbour. After a fair bit of chatting, a bill was finally enacted in 1922 by Sir George Fuller. By the time the tender had closed on 16 January 1924, more than 20 designs had been submitted from six countries. The firm of Dorman, Long & Co. Ltd., a steel manufacturer and bridge-building company from Middlesbrough, England, had even lodged three separate designs for an arch bridge, so statistically, they were in with a good chance. Bradfield and his team took four weeks to look through the submissions, with their criteria being published as Sydney Harbour Bridge: Report on Tenders. The document outlined the engineering and economic criteria used for judging, they really wanted a bridge that was to be ‘the best that engineering skill can devise’. It was the design titled ‘Design A2’ by Dorman, Long & Co. Ltd. that met the criteria and became the Harbour Bridge that we see today.

Building the Bridge

When it came to building the bridge it was Bradfield who was the civil engineer for the Public Works department and for more than 30 years he was the most active and influential person in promoting and overseeing the construction of the bridge. The bridge was part of his grand vision for electrification of the suburban railway network with a new electric train terminal at Central Station and the underground railway, but as with all important moments, there is some controversy surrounding the amount of credit he deserves for the bridge’s design.

John (Jack) Thomas Lang was Premier of NSW at the time of the bridge building and he’s the one who made things happen. He helped to raise funds for the bridge’s construction, and throughout the Great Depression he ensured the continuation and completion of the bridge by maintaining the government’s financial support for the project. This was controversial and would eventually see him fired. This was the first instance of a Premier being fired and surprisingly it wouldn’t happen again until 1975, when PM Gough Whitlam lost the top job.

In order to build the bridge, the station and wharf originally at Milsons Point would have to be relocated to Lavender Bay, just north of where you’ll find Luna Park, and this was done in 1924. An estimated 469 buildings were demolished on the bank of the north side to make way for the bridge. Which took seven to eight years to build, 53 000 tonnes of steel and 6 million hand-driven rivets were also used in the construction. With the last hand-driven rivet being driven in on 21 January 1932.

Between 2500 and 4000 workers were employed to build the bridge, a majority of the workers were Australian, but many were a mix of special skilled workers from overseas. There were stonemasons from Scotland and Italy, riggers from America, Britain and Europe, and boilermakers from Ireland and England. Most of the workers had been soldiers during the war and were given preference for employment by the government. Sadly, throughout the construction of the bridge, 16 workers lost their lives. The work they did was extremely dangerous without the same standards of Occupational Health and Safety that we see today. There is an Honour Roll of the names of those who worked on the bridge on the Pylon Lookout website.

At the time the bridge was the largest building project ever undertaken in Australia, with the granite for the pylons being quarried from Moruya, on the NSW South Coast. This granite was used for the four impressive, but decorative, 89m high pylons, which are actually made of concrete, with a granite face. Three ships were specifically built to carry 18 000 cubic metres of cut, dressed and numbered granite blocks the 300km north to Sydney. The stonemasons consisted of 250 Australian, Scottish and Italian stonemasons who lived in a temporary settlement with their families.

The foundations of the four main bearings of the bridge carry the full weight of the main span and are 12m deep, set in sandstone and filled with special reinforced high-grade concrete laid in a hexagonal formation. Strong stuff. The anchoring tunnels are 36m long and dug into the rock at each end.

The arches began to be built on 26 October 1928. They were built in halves, starting from the shore and working towards the middle. They were held up by 128 steel cable restrains that were anchored underground through u-shaped tunnels. The two steel halves of the arch met in the middle of the span on 19 August 1930, and to be super specific they touched ends at 10pm. The arch itself spans 503 metres, with the top of the arch sitting at 134m above the water. Supporting the weight of the bridge deck, the arch, oddly enough for a bridge that doesn’t open, has hinges on either end. The hinges help to hold the full weight of the bridge and spread the load to the foundations. As well as allowing the structure to move as the steel expands and contracts with the harsh Australian climate. And actually rises and falls by 18cm due to temperature changes.

On the 20 August 1930, the Australian and UK flags were flown from the jibs of the creeper cranes that were used to build the arches. The deck was put into place in June of the following year. At 59m above sea level, the deck was built opposite to the arches and started from the centre and moved out to the shore.

After seven years of construction, Dorman, Long & Co. Ltd handed the bridge over to the NSW Public Works Department on the 12 January 1932. And the electric train services ran from Central to Hornsby via North Sydney after the opening of the bridge.

It was in February of the same year that the bridge was officially load tested. All four of the rail tracks were loaded with 96 steam locomotives placed end to end. After three weeks of testing the bridge was declared safe for traffic and opened.

The official opening wasn’t until the 19th March, and wasn’t it a dramatic affair. Lang decided that he should have the honour of opening the bridge and some thought it was weird to not have a representative of the King, which would have been appropriate for the time. At the opening ceremony, Captain Francis de Groot, a member of the New Guard, had strong feelings about this, so he rode up on his horse, slashed the ceremonial ribbon and said:

“I declare this bridge open in the name of His Majesty the King, and of all decent people”.

The Captain was then arrested, the ribbon tied back together and Lang got his second chance to reopen the bridge. de Groot was declared insane and hospitalised, and worst of all, fined for the cost of the ribbon.

The total cost of the bridge was approximately 6.25 million Australian pounds (roughly $A13.5 million) and wasn’t paid off until 1988. The toll for a car was initially 6 pence (about 5 cents) and a horse and rider was 3 pence (about 2 cents). Today the toll is $3 and is used for bridge maintenance and to pay off the Harbour Tunnel.

The Pylons

The South East Pylon was opened to tourists in 1934. Archer Whithorn, a local businessman, converted the pylon into a popular tourist venue. The attractions included a camera obscura, an Aboriginal museum, a supreme café, a ‘Mother’s Nook’ where tourists could write letters home, and a ‘pashometer’ where visitors could measure their sex appeal.

Throughout the Second World War, all the tourist activities were stopped as all four pylons were taken over by the military and modified to include parapets and anti-aircraft guns.

In 1948, an ‘All Australian Exhibition’ opened in the South East Pylon and showcased informative dioramas and displays on farming, sport, transport, mining, banking and the Navy and Air Force. The Exhibition manager, Yvonne Rentoul, owned several white cats who lived in the rooftop cattery. But when Rentoul’s lease expired in 1971, the pylon was closed to the public.

But the South East Pylon had nothing to fear, for it reopened to the public in 1982 with an exhibition marking the 50th anniversary of the bridge.

In December of 1987, a bicentennial exhibition was opened, with an opportunity for surviving bridge workers to gather.

November 2000 was an important date, as after a period being closed the South East Pylon Lookout reopened to the public with a landmark exhibition called ‘the Proud Arch’.

The Bridge today

Today the bridge is a major vein throughout the city and for many is the only way to get from Sydney’s North into the CBD. It’s estimated that annual maintenance expenses for the bridge are $5 million with more than 150 000 vehicles crossing the bridge every damn day.

Painting the bridge is also an endless task. 80 000 litres of paint is required for each coat. The paint used to be composed of pure white lead and linseed oil with vegetable black to give it that grey look. This mixture is unbelievably toxic and has since become safe. The colour of the bridge is known as ‘bridge grey’, the reason the bridge is painted grey, is because when it came time to paint the bridge, it was the only colour they had enough of. It’s also been a popular myth that Paul Hogan, of Crocodile Dundee fame, used to paint the bridge.

If you cross the bridge today, you will see eight vehicle lanes, two train lanes, a foot way and a cycle way.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is an icon for the city and the country and it was for this reason that it was added to the National Heritage List on 19 March 2007.

The public were allowed to walk directly onto the deck of the bridge when it first opened in 1932 and again fifty years later in 1982. The next time that you will be able to walk onto the bridge will be at the centenary in 2032.

-

Join the Sydney Harbour Bridge 90th anniversary party - Transport for NSW

Excitement builds for Sydney Harbour Bridge 90th birthday - NSW Government

The Sydney Harbour Bridge turns 90 - The University of Sydney

Sydney Harbour Bridge opening ceremony interrupted by protester | archive, 1932 - The Guardian

In pictures: Celebrating 90 years of the Sydney Harbour Bridge - City of Sydney News

Rare Harbour Bridge photos prompt search for woman missing from history - The Sydney Morning Herald

Nine lives couldn’t save them: the cats of the Harbour Bridge - The Sydney Morning Herald

-

Disclosure: As an affiliate marketer, we may receive a commission on products that you purchase through clicking on links within this website.