Great Ocean Road

Our journey sees us along a road, quite a long road, but one with some of the best views you can find.

Along the way we’ll learn about the local Indigenous people, the people who built the road, the people the road is dedicated too, and some of the natural formations that make the road the tourist hotspot it has turned out to be.

Before the Road

In south-west Victoria, along Australia’s southern coast, you will find an unforgiving coastline. Long before the Europeans wandered past, the coastal regions were populated by the clans of the Wathaurung, Gadubanud and Gunditjmara tribes, to name a few. These ancient nomadic people would harvest their food from the surrounding bush and the sea.

And it was from the sea that the Europeans arrived. They entered Port Phillip Bay in late 1801, but rough weather and a dangerous entrance to the bay meant that large numbers of settlers were delayed. It wasn’t until 1802, that Lt. John Murray claimed possession of the land for Britain, initially calling the area, Port King. Port King is a bit of silly name, so it was later renamed to the current Port Phillip after Captain Arthur Phillip, the chap who led the First Fleet from England to Australia in 1788.

By the late 1840s, the landscape was almost entirely changed, at least the use of the land was. Sheep and cattle farmers used large runs behind the Otway Ranges to move their herds around and timber cutters were going to town on the area that we now know as Lorne and Apollo Bay.

Small towns and settlements had popped up all along the south-west coast of the state, but to travel between them was far from a joy. The whole area was dominated by thick bush and massive rocks, with some parts only accessible by sea, and others having the pleasure of a bush track that was rough going. You were welcome to travel between towns, but it would be slow and laborious, taking weeks to make your way through the thick bush along a poorly made coach track. What I’m sure was a godsend to the people at the time, a railway was built in the 1870s, but it only went from Geelong to Winchelsea, which today is about a half hour drive, so not really that helpful for anyone living further west than Winchelsea, which would have been a fair amount of people.

And so, the demand for a road or a rail that connected the isolated coastal communities began to grow louder and louder. It wasn’t even smooth sailing, if you decided to go via sea, the coast is treacherous going, and there were several famous shipwrecks throughout the area. Finally, initial plans for a road started to gain traction in the 1880s, as the 20th century drew closer, E.H. Lascelles and Walter Howard Smith, businessmen from Geelong, proposed a road that would take travellers from their town to Lorne. But nothing really happened until the end of the First World War.

It was with the formation of the Country Roads Board in 1912, that a great big leap was taken in making the Great Ocean Road a reality. The Road was expected to be a link between isolated communities along the coast, providing vital transport for the timber and tourism industries.

The War

Once the First World War had settled and the soldiers had started returning home, William Calder, Chairman of the aforementioned Country Roads Board, thought that a great way to keep the soldiers busy and occupied would be to get them building something. And what better than some roads. So Calder set to work. First he contacted the State War Council and put his idea to them in the form of a proposal for funds. He also submitted a plan that he called the ‘South Coast Road’, which would stretch from Barwon Heads, south of Geelong, follow the coast around Cape Otway and out through to Warrnambool.

Cr (Councillor) Howard Hitchcock, Geelong Mayor at the time, thought Calder’s idea wasn’t a bad one, and thought it could definitely encourage more people to pop in to Geelong. And since soldiers were going to be building the road, why not dedicate the road to their mates who had fallen in the war.

Not everyone was a fan though. Some thought that getting soldiers to build something after they’d just fought for our freedom was a bit much and could be potentially seen as a ‘punishment’. Some thought it would be more appropriate to use prisoners, because we are a convict nation. But then it was realised that the air on the coast is pretty good. You can swim and fish and shoot and generally have a good old jolly time. No, prisoners don’t deserve that kind of luxury, our returned soldiers it is.

The Great Ocean Road Trust

And so The Great Ocean Road Trust was formed on 22 March, 1918. It was at a meeting of 500 people in Colac that Hitchcock was elected as President of the Trust, and $300 000 was put aside for the construction of the road, that originally was set to run for 160 km. But again, not everyone was thrilled. There some people in the surrounding councils who decided they didn’t have any money ‘to waste on tourists’.

There were a couple of reasons to build the road though. The first one was to provide employment for soldiers returning from the war and allow them to build a monument to those who had fallen fighting for their country. The second, was to provide an easier route of travel for those needing to go between coastal towns. And the third was tourism, as we in a world brought to a quick stop by a virus know only too well; cashed up tourists, they do wonders.

There was even a brochure made up to educate people on the vision of the soon to be road. The Great Ocean Road was a

worthy memorial to all Victorian soldiers and a national asset for Victoria. The carrying out of this scheme would provide the finest ocean road in the world. Travellers throughout the world know of nothing which would compare with it.

The Trust decided that the stage of the road that went from Lorne to Cape Patton, a distance of about 28 km, would be built first.

Building the Road

Before the road could be built, the land needed to be surveyed and the path that the road would take pegged out. And so this fell to a party of returned soldiers who were led by Warrant Officer John Hassett. They started in August of 1918 and it was initially expected to take about 3 months for the team to mark out the path of the road, but next thing they knew it was March 1919, and they had only done about 16 km and it had been tough going due to the difficult terrain. This would only be the beginning, without the help of heavy machinery, everything would have to be done by hand, they only had the use of picks, shovels and horse-drawn carts. Later they would have the help of detonating charges, but according to Peter Spring, a member of the Lorne historical society,

there were no explosives used in the first few years, mainly because a lot of the servicemen returning from war were suffering from shell shock. It was hard work done by hand.

But on 19 September, 1919, the Victorian Premier, a Mr Lawson at the time, officially launched the project when he set off a series of charges near Lorne. During the 13 years it took to create the road, nearly 3000 returned soldiers worked on the Great Ocean Road. But the difficult and dangerous nature of the work meant that turnover was high, at some points there only a couple dozen working on the road, at other times hundreds. The soldiers weren’t paid much considering the conditions. Just 10 shillings and sixpence, which would be just over a dollar for us, for and eight-hour day and they were expected to work a half-day on Saturdays.

They set up bush camps near the construction areas, where each man had an individual tent along with a communal dining marquee and a kitchen. Although the soldiers did make good use of their surroundings, they enjoyed the simple pleasures like swimming, fishing and hunting. The camp even came with a piano, gramophone, playing cards, games, newspapers and magazines. And they took advantage of every situation. Especially when an old steamer named The Casino became stranded after hitting a reef near Cape Patton in 1924. In order to get floating again the crew had to forgo some of its cargo over the side. Lucky for the soldiers this cargo was 500 barrels of beer and about 120 cases of spirits. So naturally everyone took an unscheduled drinks break, the fact that this particular break lasted two weeks didn’t seem to bother anyone.

The openings

The Great Ocean Road has had a couple of openings. The first one was when the Lorne to Eastern View section of the road was officially opened on 18 March, 1922. Nearly 80 cars full of tourists travelled to Lorne to witness the official ceremony. But the road’s opening was short-lived. On the 10th May the road had to be closed so that the last little bit could be finished.

It was reopened on 21st December, and this time they had snuck in some tolls in an effort to recoup construction costs. Anyone driving a motor had to pay two shillings and sixpence, about 25 cents, and a wagon with more than two horses could go through for one shilling and sixpence, about 15 cents. But despite the tolls, the road proved amazing popular, with the tolls raking in about £250 in the first four weeks. Not bad, not bad. The tolls continued to bring in the cash for the next 14 years, but once the Trust had dissolved, and the Great Ocean Road was handed over the Victorian State Government in 1936, the toll booths disappeared as well.

Workers carried on for the next 10 years, completing the road along the coastline, with thousands of tonnes of rock dropped into the ocean as slowly but surely a path was forged.

Finally on 27 April, 1932, the Trust announced that the entire road was completed and a second official opening was to be held. This completed road now extended all the way over to Warrnambool. It was on the 26 November, 1932 that an entire weekend was put aside for this momentous occasion. It was the Lieutenant Governor, Sir William Irvine, who officially declared the Great Ocean Road open. The ceremony was held near the Grand Pacific Hotel in Lorne, which was where the first survey peg had been hammered into the ground on that very first day 14 years ago. The Age even had something to say about the occasion:

In the face of almost insurmountable odds, the Great Ocean Road was materialised from a dream or ‘wild-cat scheme’, as many dubbed it, into concrete reality.

Unfortunately, Hitchcock, the man who had kicked everything off passed away from heart disease in August of 1932, just before the ceremony. To honour him, his car was still driven behind the governor’s in the opening ceremony precession along the road. And there’s even a memorial to him at Mt. Defiance, near Lorne. He’s also still considered to be the ‘Father of the Road’.

As we already know, the Great Ocean Road was gifted to the government by the Trust, with the deeds being presented to the Victorian Premier at a ceremony just for the occasion at the Cathedral Rock toll gate. In its original state, the road was pretty impressive, only being able to fit a single vehicle comfortably at a time. There were extremely hazardous areas of sheer cliff faces and only a few spots to pull over to allow someone to pass coming the other way.

The memorials

The Great Ocean Road is recognised as the largest war memorial in the world and honours those who lost their lives in the First World War.

There’s a memorial wall and tablets at Mt. Defiance, these were unveiled in 1935. We already know about the one for Howard Hitchcock, but there’s also one there for all the men and women who served in the Great War.

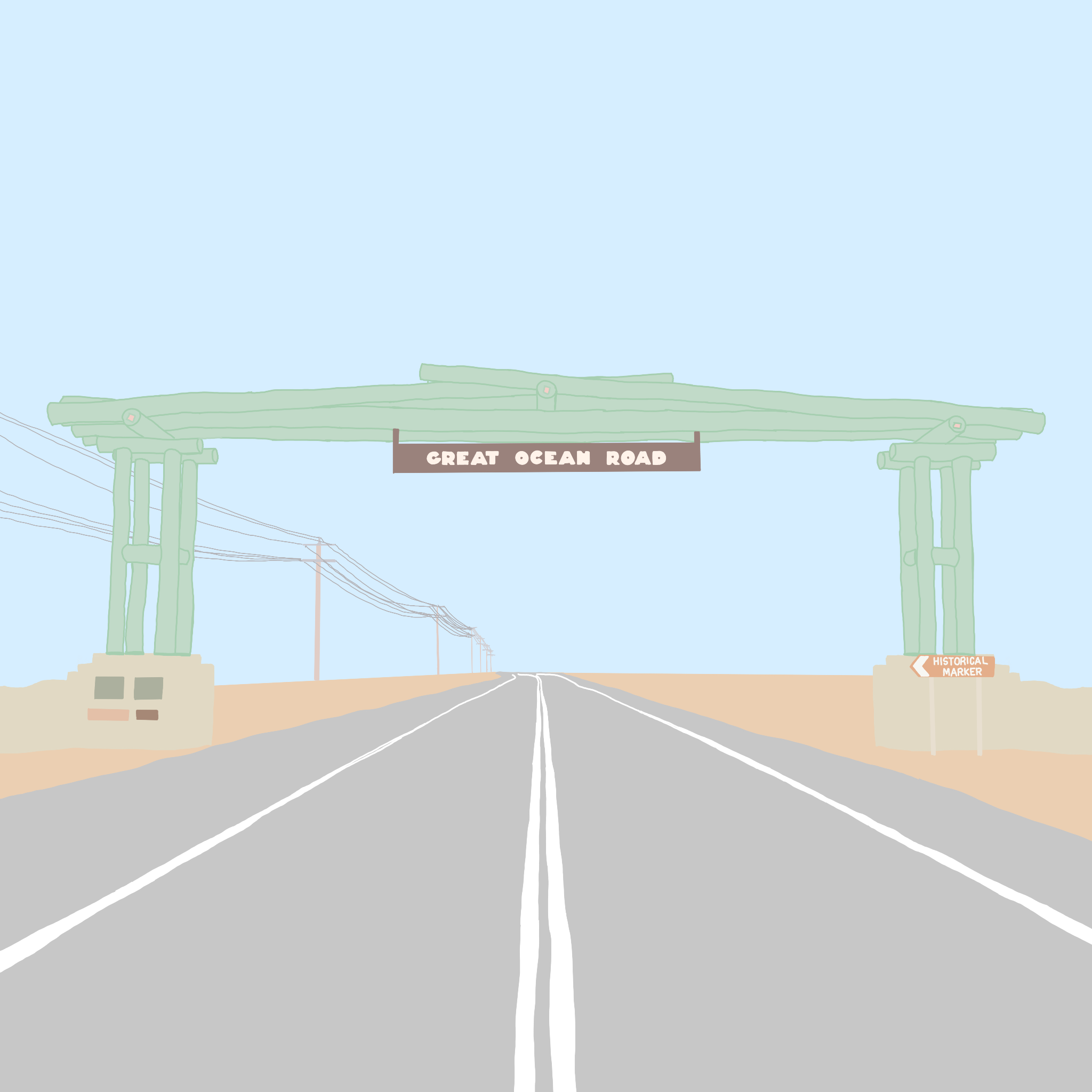

There have also been four memorial arches that stand over the Great Ocean Road and is quite the tourist hotspot. The initial arch was where ‘The Springs’ toll gate used to be, near Cathedral Rock. It had the words ‘Returned Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Great Ocean Road’ inscribed upon it but was demolished in 1936 with the removal of the tolls.

The first to be built at Easter View was erected in 1939. This arch was around until 1970 when the Country Roads Board flagged it as a potential traffic hazard due to its narrowness and proposed that it be demolished. People weren’t best pleased about this, but the Roads Board needn’t have worried because one day, along came a truck that pulled the arch down free of charge. The second arch at Eastern View was put in place in 1972. It only lasted about ten years until the Ash Wednesday bushfires made quick work of it in February of 1983. Initially the thought was to not replace the arch, the previous ones hadn’t had the best of luck, but the public strongly felt that the arch should be replaced, and so in the exact same spot, you will find an arch today welcoming you to the Great Ocean Road.

The arch itself is made of timber with cement and stone supports on either side of the road. A plaque was also put in, in 1939 commemorating not only those who lost their lives throughout the war, but remembering those who returned and built the road, quite literally, with their bare hands.

Great Ocean Road today

1962 was a pretty good year for the road, as the Tourist Development Authority decided to deem it one of the great scenic roads of the world. Quite a title. In order to improve traffic, sections were also widened between the Lorne Hotel and the Pacific Hotel. But despite these improvements, the road was known to be quite the challenging drive, so much so that the Victorian Police Motor School used it to train their officers in precise driving until around 1966.

Despite all the prestige, the Great Ocean Road is still vulnerable to something that none of us can get away from, the natural elements. 1960 saw a section of road near Princetown partially washed into the ocean after a particularly bad batch of storms. And in 1964 and 1971, there were severe landslides that closed sections of the road near Lorne. The Road has also been closed several times to bushfires that have come a bit too close, easy enough mistake for the bushfires to make when one side of the road is the ocean and the other side is thick brush. More recently in 2011, a heavy bout of rain meant that some of the overhanging cliffs had collapsed, again closing part of the road.

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom in 2011, that was the year the Road was added to the Australian National Heritage List, so it will be preserved forever and ever. And it was much more recently in 2019, that 100 years was marked since the construction of the road had started all those years ago.

There was also a push in 2019 to reintroduce the tolls. Many locals feel heavy tourism, especially in the form of heavy 50 to 60 seat coaches, are starting to cause damage to the road. With one local suggesting to The Guardian:

You’re passing through a national park to get here. Virtually everywhere else in the world where you enter a very popular national park you pay a fee. Every tourist who comes down that road should be paying at least $20.

It’ll take you about 90 minutes to get from the centre of Melbourne to Torquay, where the Great Ocean Road starts. The road that you will drive on today has amazing views of the Bass Strait and Southern Ocean, and can proclaim to be one of the most photogenic coastlines in the world, just have a scroll on Instagram and you’ll know what I mean. Along the way you’ll see, among others, formations such as Loch Ard Gorge, the Grotto, London Bridge, which had to be renamed London Arch after the ‘bridge’ partially collapsed, and, probably most famous of all the Twelve Apostles, which more accurately should be known as the Eight Apostles, because we may have lost a couple to erosion.

The entire region is thick with maritime history and this heritage is still visible through the lighthouses that continue to dominate the landscape along the road. There are also fascinating Aboriginal historical and sacred sites to visit, along with maritime museums and even shipwrecks.

You can even go on a tour with a local guide, who can teach you about the heritage of the Gunditjmara people as you observe native wildlife and have a bit tucker in the form of bush foods.

And if you go a bit further than the Great Ocean Road, just past Warrnambool, you’ll find the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, a UNESCO World Heritage Centre, near Lake Condah, where, flying in the face of convention, you’ll find a permanent Aboriginal settlement. Meaning that not all Indigenous tribes were nomadic people.

Known as the shipwreck coast, Victoria’s southern coast is pretty treacherous, with more than 200 shipwrecks lying off the coast. Explorer Matthew Flinders is even reported as saying all the way back in 1802, that he had

seldom seen a more fearful section of coastline.

One of the more famous shipwrecks is that of Loch Ard, which wrecked near Port Campbell in 1878 on its way to Melbourne from England to drop off stuff meant for display at the 1880 Great International Exhibition. Take a visit to the Flagstaff Hill Maritime Village to learn all about it, you can even visit some historic lighthouses there. And if you haven’t yet, listen to our episode on the Royal Exhibition Building for more on the International Exhibitions that took over Melbourne.

Torquay even has its very own Australian National Surfing Museum, the world’s largest surfing museum in fact. You can check out how surfing boards developed and changed throughout the years, see films of the great surfers and experience how surfing has impacted and affected Australian culture and the Australian way of life.

And in the Lorne Visitor Centre there is a permanent exhibition honouring the diggers that created the Great Ocean Road, and showing just how treacherous the conditions that they worked in were.

When you drive along the road today, you will find a two lane road, one lane for each direction, going from Torquay for about 243 kms until you end up in Allansford, just short of Warrnambool. On the left side you’ll see the Southern Ocean and on the right you’ll see pretty much just bush.

Known as one of the best coastal road trips in the world. The Great Ocean Road holds a special place in the heart of Cadel Evans. Even though he’s ridden his bicycle around the world and even won the Tour de France in 2011, he reckons riding along the Great Ocean Road is one of his favourites.

It is so spectacular. You don’t realise how good this country is until you live overseas – the smell of the eucalypts, the clear skies, the people are friendly and when the sun is shining, it is just beautiful.

There’s a brilliant miniseries called ‘The Story of the Road’ done by Great Ocean Road Regional Tourism. And it is fantastic, it shows you how the road came about from its construction, and the lives of the returned servicemen who built the road. The series is made up of five, five-minute films that

connect people with the towns along the Great Ocean Road by sharing stories of indigenous history, the diggers making of the road, community and what the region is known for today.

-

Aboriginal Culture on the Great Ocean Road - Responsible Travel

Australian National Surfing Museum

The Story of the Road - Visit Great Ocean Road

Great Ocean Road upgrades welcomed - ABC News

Great Ocean Road Activity Book - The Standard

Reducing bushfire risk for Great Ocean Road communities - Mirage News

A Road-Trip Guide to the Great Ocean Road - Broadsheet

The Coast Diaries: Loving the Great Ocean Road to death - The Age

Photo story: Australia’s Great Ocean Road - National Geographic

The story of the Australian veterans who built the Great Ocean Road - SBS

-

Great Ocean Road: History and Heritage - Visit Victoria

Building the Great Ocean Road - Visit Melbourne

The History of the Great Ocean Road - Lorne Historical Society

Guide to the Great Ocean Road - Australia.com

The Story of the Road - Visit Great Ocean Road

Great Ocean Road feeling the strain - The Guardian

Australian National Surfing Museum

Great Ocean Road History - Go West Tours

The Great Ocean Road’s History - Bunyip Tours

Who built the Great Ocean Road - Sightseeing Tours

Great Ocean Road History - Visit Otways

History of the Great Ocean Road - Visit Great Ocean Road

Aboriginal Culture on the Great Ocean Road - Responsible Travel

Disclosure: As an affiliate marketer, we may receive a commission on products that you purchase through clicking on links within this website.