Lucerne Lion Monument

A Lion with the emotions of a nation.

Let’s take a wander over to Lucerne in Switzerland. Our destination has some political intrigue behind it and was created as a memorial to fallen soldiers and has since become a national monument of remembrance. I’ll take you through the history of a gorgeous piece of art that has brought people to tears for its life like representation of pain and fear.

Monumental facts

To start with today, I’ve got some monumental facts for you.

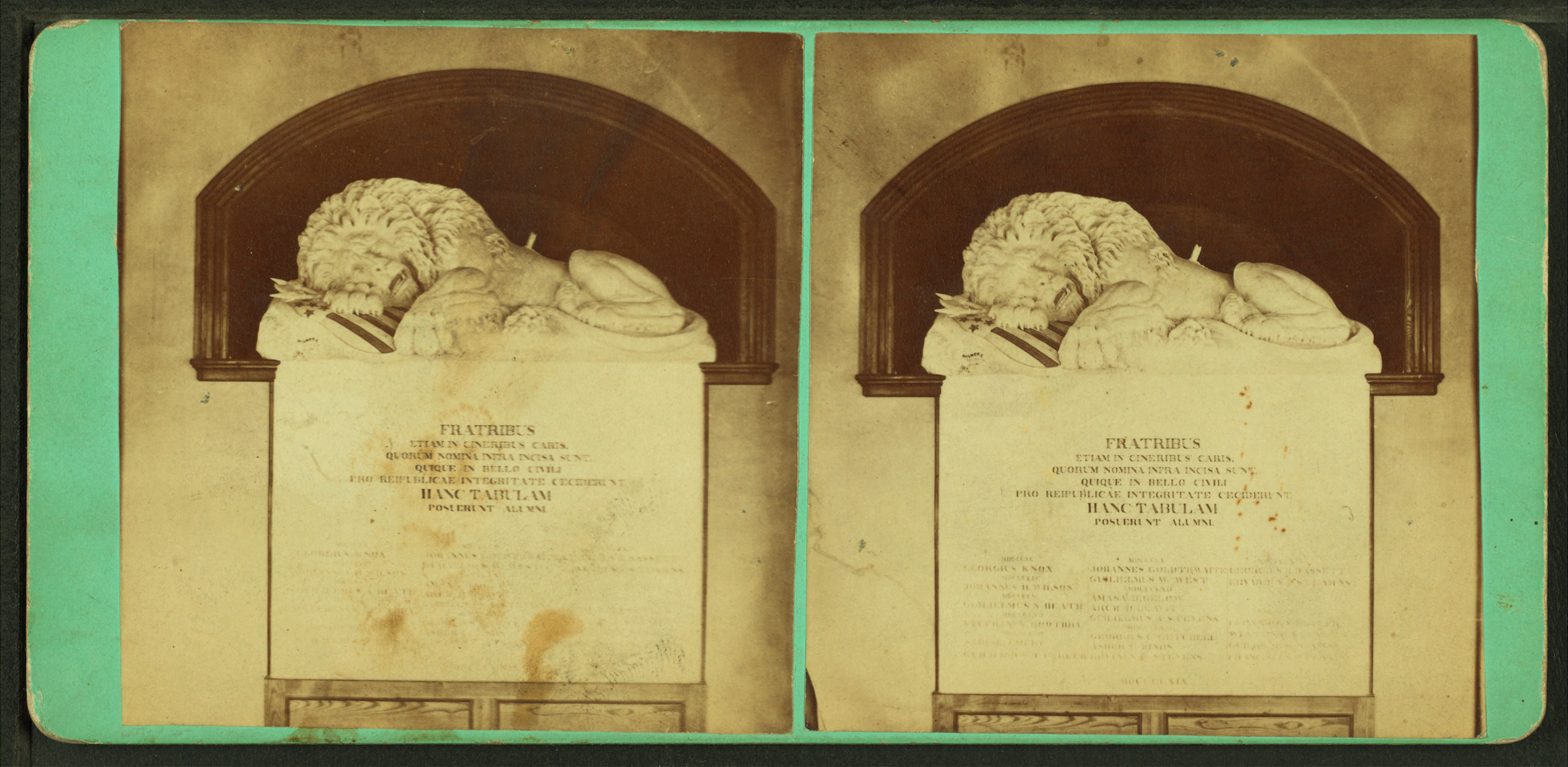

So the Lion Monument features a giant dying lion carved into a wall of sandstone rock that sits above a pond that you’ll be able to find on the outskirts of Lucerne.

The wall is the last remaining reminder of a former Sandstone Quarry that was used for centuries to build Lucerne itself. The owner of the land and commissioner of the monument had the land remodelled to resemble an English landscape garden, including the small quarry lake which remains to this day.

Etched into the stone in 1820, the sculpture measures 10 metres in length and six metres in height. Above the lion is inscribed the words:

HELVETIORUM FIDEI AC VIRTUTI,

which translated from the Latin says:

To the loyalty and bravery of the Swiss.

And below the Lion’s niche can be found a list of the deceased officers’ names being remembered. You will also see a death toll of 760 and the number of surviving soldiers, 350, both written as Roman numerals.

Upon his visit, Mark Twain described the monument in his 1880 travelogue, A Tramp Abroad, as ‘the most mournful and moving piece of stone in the world’.

What happened to get a monument?

So the story behind the Lion Monument starts all the way back in the 15th century, when the long tradition of Swiss mercenary soldiers begins.

As mercenaries, Swiss Guards were renowned for honouring their agreements and their loyalty towards their employers. The French Royal Family has been recorded as hiring these mercenaries since the 17th century. The soldiers were known for serving foreign governments and were renowned for their honour and valour. Their reputation kept them in high demand particularly in France and Spain throughout Early Modern Europe.

It was on the 10 August 1792, that saw a mob of revolutionary masses storm and attack the royal Tuileries Palace. This event is now known as the ‘August Insurrection’. At the time of the Insurrection, there was a regiment of 1000 Swiss Guards serving King Louis XVI. A couple of days earlier, 300 of the Guards had been sent on a mission outside of Paris, leaving 700 to defend the King and his family.

True to their reputation, the Swiss Guards defended their employers against the angry Parisian mob. The Guards attempted to defend the royal family and fought to hold off the mob so that they could escape. It was during this conflict that a majority of the guards were killed, some also succumbed to their injuries after being caught and put in prison, with others becoming victims of the famous guillotine.

The Lion Monument was created as a memorial to the 700 Swiss soldiers massacred throughout the August Insurrection during the French Revolution.

It was an officer of the Swiss Guards, second lieutenant Karl Pfyffer von Altishofen, who was comfortably home on leave in Lucerne when his comrades were killed in Paris.

Pfyffer remained in service until 1801, when his regiment disbanded and he returned home to Lucerne. Pretty much straight away he began preparing plans for a monument that would honour and memorialise those who fell in Paris. But because of a fair bit of political unrest, there was a bit of to-ing and fro-ing in order to get his idea up off the ground. Because of the political climate, Pfyffer was forced to keep his plans a secret, until Switzerland was in a more stable political state. Whilst Switzerland was under French rule, a monument dedicated to the defenders of the monarchy, probably wouldn’t be the best idea. It wasn’t until 1815, once the Swiss had regained their independence that Pfyffer was able to make his plans public.

Carving

The monument was designed by Bertel Thorvaldsen. He was a Danish sculptor who was commissioned by Pfyffer to design the monument in 1819, while he lived in Rome.

The original brief for the design was a dead lion surrounded by broken weapons, but Thorvaldsen didn’t fancy the idea of a dead lion and wanted to depict a living lion. So like all good relationships they compromised and settled on a dying lion. There was just one small, inconsequential issue. Thorvaldsen had never seen a lion himself. So he used his powers of observation and was forced to rely on illustrations.

Pfyffer also put out a public appeal for funds for the monument. And for the youth amongst us, basically he did the original GoFundMe. A whole heap of people contributed to the public appeal, but there were quite a few who didn’t. Those who found themselves in pro-democracy circles, sort of criticised the monument as a tribute to royal power. And it was this disapproval that meant at the end of the day Pfyffer hadn’t raised enough funds to hire Thorvaldsen. He didn’t let this get in his way though, because he ended up hiring Thorvaldsen anyway.

If you look at The Thorvaldsen Museum Archives, they’ll tell you that Pfyffer had deliberately hidden the fact that he didn’t have the money to hire the artist until after he had received the model of the sculpture. This pretty much caused the relationship between the men to fall apart. No one likes to be taken advantage of and lied to. Thorvaldsen decided to take his sweet time in delivering changes to the sculpture and these delays frustrated Pfyffer, who was irritating Thorvaldsen who hated feeling rushed. When Thorvaldsen learnt the truth about the whole money situation, he made some very cheeky last minute changes to the sculpture. Which (cliff-hanger) we’ll come back round to a bit later on.

Once Pfyffer was in possession of the model of the sculpture, he originally assigned Swiss sculptor, Pancras Eggenschwyler, the task of carving the lion into the cliff face. Using Thorvaldsen’s model as a guide of course. Sadly, whilst working on the monument, Eggenschwyler fell from the scaffold and died. Lucas Ahorn, from Germany, was the replacement stonemason asked to complete the sculpture. He carved the monument out of the sandstone rock from 1820 and completed the lion in 1821.

The Lion itself

When looking at the lion itself, the casual observer will see a dying animal, with the head of a spear sticking out from its side. It is this spear that is the cause of the animals suffering and eventual death. Pain is etched into the lion’s face and his posture.

The dying lion symbolises the soldiers’ courage, strength and willingness to die rather than betray their honour and oath of service.

The lion lays partially covering a shield bearing the fleur-de-lys, representing the French monarchy. Beside the lion is another shield bearing the Swiss coat of arms.

Traditionally the lion symbolises those at the top of society, the kings, the princes, the popes. But Pfyffer wanted the Lucerne Lion to embody the bravery, fidelity and courage of the Swiss soldiers instead of the strength of monarchical power. Hence why Louis XVI and the French monarchy is represented by the French coat of arms. The ‘passive’ shield can’t protect itself, it has to be protected. This leads the viewer to conclude that it was not the act of the king or the monarchy that was heroic, but that of the defending Swiss soldiers. This view then allows us to see the monument in a much more modern light. One that highlights monarchical power as not especially glorious, but gives courage and power to the ordinary man.

Feuding between frenemies

Coming back to the issue Thorvaldsen had with Pfyffer. The casual observer will see a lion dying in a crevice on a rock face. The keen observer will see two animals carved into that rock face.

As pretty much all of us would be, Thorvaldsen was pissed off about not being paid correctly, so he decided to make his feelings known by making some last minute changes to the sculpture. Out of respect to the fallen soldiers he didn’t touch the lion itself, but, he changed the shape of the alcove where the lion lays dying. Take a step back and look at the lion and the rock face as one, and a familiar form will start to take shape. That’s right. Thorvaldsen changed the shape of the alcove to the outline of a pig. Supposedly no one noticed this pig shape alcove (or no one mentioned it to the boss) until the sculpture was completed. This was a subtle but clear message expressing Thorvaldsen’s disdain about the way things ended with Pfyffer.

[This turn of events that made Thorvaldsen change the alcove into a shape resembling a pig is believed to be myth and not substantiated by either Thorvaldsen or Pfyffer’s records. But this is in essence what history is, myths are proven or disproven, things we once believed to be true are found to be false, or vice versa when new evidence is unearthed, changing our perception of history.]

What happened next

Once completed, the Lucerne Lion was dedicated to the fallen soldiers on the 10 August, 1821. The 29th anniversary of the storming of the Tuileries Palace.

At the unveiling, there were some that were outraged about the lack of Swiss nationalism associated with the monument. Despite the entire monument being dedicated to Swiss soldiers. Swiss pro-democracy peeps saw the monument as reactionary and royalist. Because the soldiers fell in defence of Louis XVI, the monument must therefore be a glorification of absolute monarchy. Pro-democratic and liberal sympathetic students even organised a counter-demonstration during the monument’s dedication ceremony. And newspapers reported violent street protests and democratic attempts to destroy the monument. It took several years before the monument started to be seen for what it was, a symbol of spilt Swiss blood, and finally started becoming a national memorial.

Slowly but surely, the monument’s meanings and associations started to move away from supporting the memory of an absolute monarchy, or even associations with the French Revolution. Instead, it began to represent a tribute to ‘a bravely fought, freedom-loving people’. Perhaps even connecting itself to a utopian democratic future. One where the people, and not the elites of society, are given the highest importance.

The land that the monument stands in was originally private property owned by Pfyffer himself. He designed the landscape and would charge people a fee to come and see the lion. The City of Lucerne bought the land in 1882, making the site accessible without an entrance fee. The monument soon became a major tourist attraction, with souvenir shops nearby, and you can even still see the old ticket booth at the entrance to the monument.

So if you find yourself in the area, pop on over, and marvel at the wonder that is the Lion Monument.

Disclosure: As an affiliate marketer, we may receive a commission on products that you purchase through clicking on links within this website.

-

Switzerland’s beloved Lion Monument in peril - OnManorama

Swiss pond fishers give new meaning to concept of 'money laundering' - The Local

The Lion of Lucerne: the controversial tourist attraction - SwissInfo

Lucerne art installation highlights coral bleaching - SwissInfo

Switzerland’s Lion Monument threatened with decay - Gulf Today

-

Lion of Lucerne - Atlas Obscura

Unravelling the tragic story behind the impressive Lion Monument of Lucerne - Ancient Origins

The Pig of Lucerne - Amusing Planet

Lion Monument or Dying Lion Monument in Lucerne Switzerland - Nelmitravel

Lion Monument - All About Switzerland

Lion Monument: a memorial exuding the portent of loss - Lucerne

Lucerne: a short history of The Lion Monument - Mark Sukhija

Dying Lion (The Lucerne Lion) - The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives