Gregorian Calendar

Today we digress to talk about how calendars change, and why they change, and why is it always the pope that changes them?

The Julian Calendar

The Julian calendar was first used by Julius Caesar in 46 BC, so I guess you could say it’s been around for a little while.

Up until this point the Roman calendar was a real mess, every now and then extra days were tacked on depending on the politicians in power at the time, and it was mainly based off the phases of the moon. But it was far from reliable.

Julius Caesar decided enough was enough and it was a time for a more consistent way of tracking time. So he got to work sorting it out, and by ‘got to work’ I mean he hired an astronomer out of Alexandria. History tells us this astronomer was named Sosigenes and he was able to create a calendar that was based off the Earth’s revolutions around the Sun.

While this was a terrific idea, there was one tiny little problem. The solar year is 365 ¼ days, which means that a ‘leap day’ would have to be added to the calendar every four years in order to keep the seasons happening at the same time each year.

And while this makes sense, there was another tiny little problem. Four years is way too often, and pretty soon the Julian calendar was out of sync with stuff like equinoxes and solstices, which was exactly what Caesar was trying to fix.

This meant that by the time we get to Pope Gregory XIII in the 1500s, Easter, which is meant to fall on 21 March, is not happening in conjunction with the spring equinox. And so the good old Pope decided to create his own calendar. One that would make Easter happen at the right time.

The need for change

So thanks to Caesar’s Julian calendar drifting out of sync, by the 1500s the calendar is 14 days off. Which means that the Gregorian calendar was simple enough to sort a fix. Just go back 14 days. Easy.

But Pope Gregory needed to ensure that this new calendar wouldn’t drift off course again, so a new formula was calculated for leap years, and it’s a little bit more complicated than the easy ‘every four years’ rule.

The new formula went a little something like this:

- If the year is divisible by 4, then there IS a leap year,

- Except if its divisible by 100, then NO leap year

- But if the year is divisible by 400, then there IS a leap year.

That’s not complicated or confusing at all.

Although this complicated formula does fix the drifting found in the Julian Calendar, and even though this new calendar, the Gregorian calendar, is named after Pope Gregory XIII, we actually have Luigi Lilio, sometimes known by Aloysius Lilius, an Italian doctor, astronomer and philosopher, to thank for this little fix. The sad news is that this brilliant man died in 1576, six years before the Gregorian calendar was officially introduced, which meant he never got to live in a time of his own devising.

The swap

Okay great, we’ve sorted the new calendar so that it’s not drifting all over the place. But how to get the rest of the world using it?

When the Pope declared that in October 1582, 10 days would be skipped there were some that were onboard and others that were severely sceptical.

Naturally Catholic countries such as Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, parts of France and even the Roman Catholic parts of Germany were early adopters of the Pope’s new timekeeping.

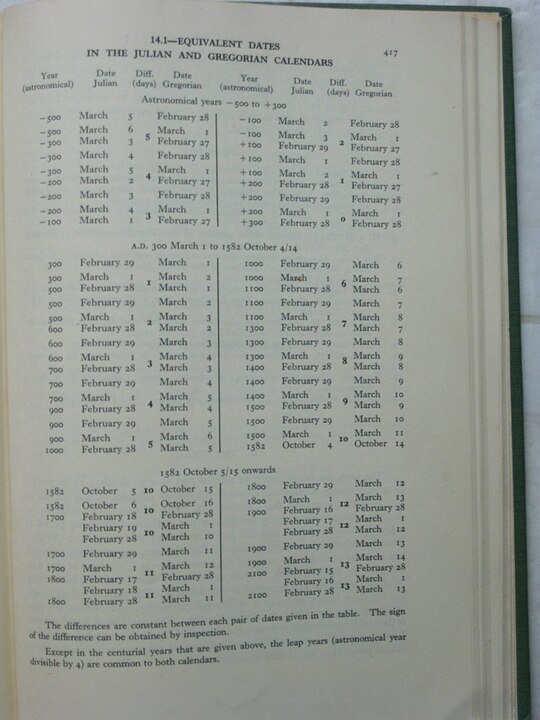

But for those who switched over later on, it meant that the discrepancy between the Julian and Gregorian calendars continued, so they would have to skip more days than the original 10.

It actually took almost 200 years for England to see the error of their ways and change over, which they and all their colonies did back in 1752. Here’s Benjamin Franklin’s thoughts on the switch:

And what an indulgence is here, for those who love their pillow to lie down in Peace on the second of this month and not perhaps awake til the morning of the fourteenth.

Now that’s what I call a sleep in.

Gradually the other countries of the world slowly adopted the trendy Gregorian calendar, Sweden in 1753, Japan not until 1873, China in 1912, Soviet republics in 1918, and interestingly Greece finally got round to changing over in 1923, talk about a late adopter.

In the end it took over three centuries for the world to accept and use the Gregorian calendar. Although there are some out there that use older calendars still. Orthodox churches still follow the Julian calendar, and while Islamic countries use the Gregorian calendar for secular life, there are many Islam based calendars that are still used for religious purposes.

Living with the Gregorian Calendar

These days the Gregorian calendar is the one that’s internationally accepted. We know it’s based on a solar year that’s divided into 12, if a little roughly, and even though the Gregorian leap year formula is much better than the Julian calendar’s attempt, it’s still not perfect.

It’s still off by 26 seconds, which means that by the time we get to the year 4909, the Gregorian calendar will be an entire day ahead of the solar year. So that’s something to look forward to.

There have been some suggestions about how to correct this egregious error. Some claim that the way the Gregorian calendar is structured, means that holidays falling mid-week is costing businesses fiscally. So two blokes out at the Johns Hopkins University, Steve Hanke and Richard Henry, proposed the Hanke-Henry Permanent Calendar. This calendar is a unique one in that every year is the same, so the same date will fall on the same day, for example October 4 will always be a Wednesday.

But then what about the leaps years, you might be asking yourself, well they’ve thought of that too. Every five or six years we would have a ‘leap week’ to put us back in line with the solar year.

While this and other calendars are yet to catch on, there’s only one thing that’s for certain. Calendars are merely a construct, clearly not very accurate ones, and anyone can create their own way of keeping time. Everyone else using the same one you use though, that’s no guarantee. Unless perhaps you’re the Pope.

-

-

Gregorian calendar - Britannica

The Gregorian Calendar - Time and date

Gregorian calendar reform: Why are some dates missing? - Time and date

6 things you may not know about the Gregorian calendar - History

The Gregorian Calendar - Encyclopaedia Virginia

We’ve been using the Gregorian calendar for 434 years - Vox

The Gregorian Calendar Adopted in England - History Today

The geopolitics of the Gregorian Calendar - Worldview

Gregorian calendar history, format and uses - Study.com

18 Gregorian calendar facts you need to know - Calendar

Hanke-Henry Permanent Calendar - HHOT

The Julian calendar - Time and date

Julian and Gregorian calendar systems: overview and differences - Study.com

Disclosure: As an affiliate marketer, we may receive a commission on products that you purchase through clicking on links within this website.