Culloden Battlefield

Let’s wander back to a time when monarchs could be overthrown and then restored.

The Battle of Culloden claims to be one of the last places a fight to restore a monarch took place. Let’s discover the result of that fight and how the aftermath affected the local people.

The context of the battle

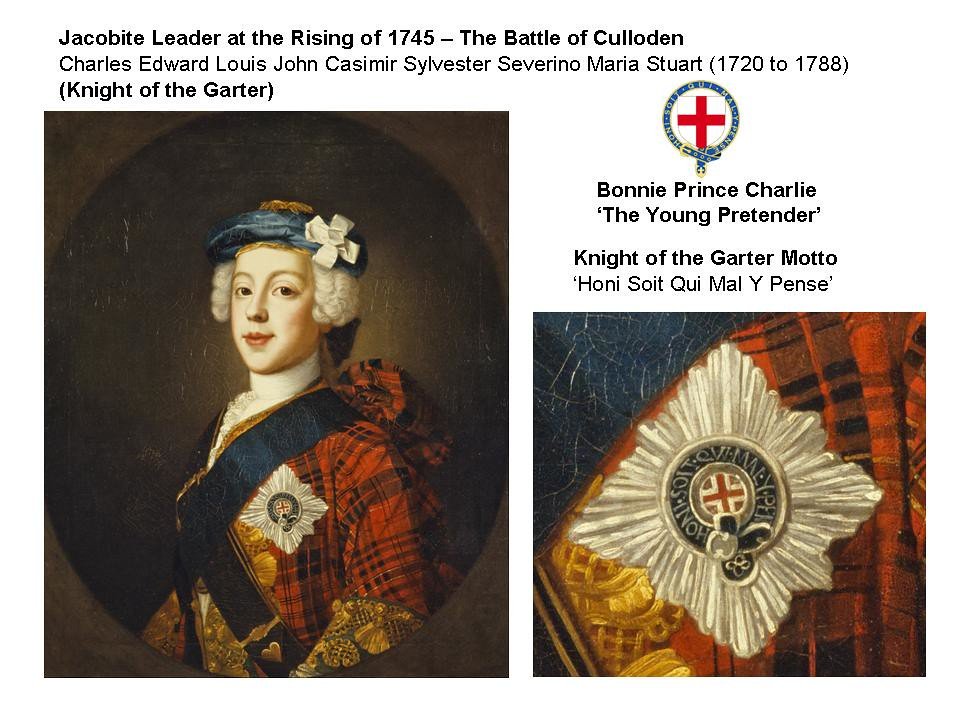

The Battle of Culloden, which can sometimes go by the Battle of Drummossie, took place in 1746, but is actually the final confrontation of the Jacobite Rising of 1745, where a group of Jacobites, fighting for the Young Pretender, a young Charles Edward, were defeated and, for lack of a better word, slaughtered by the men of the Duke of Cumberland, William Augustus.

The Jacobite Rising had been an attempt at restoring a Stuart monarch to the throne in the shape of Bonnie Prince Charlie, which is what the young Charles went by, to the British throne. But it wasn’t that easy, George II, the sitting King, made sure that the men fighting for Cumberland were well financed and therefore supplied. Unfortunately the Young Pretender could not ensure the same.

Culloden itself is really just a tract of land not too far from the town of Inverness. But the battle itself took place on Drummossie Moor about 10 km east of Inverness. Hence the battle that took place on the moor sometimes being called the Battle of Drummossie.

Before the uprising, in the early 18th century, there was somewhat of a divide between the highlanders and the lowlanders of Scotland. The lowlanders, those living south of Dumbarton all the way over to the Firth of Clyde were exposed to a lot more English influence, which was naturally reflected more in their culture, language and politics than the highlanders, who were mainly Gaelic Scots and due to living so far north were less affected by English influence on their aspects of life.

The Highlanders by this time were following the clan system. It had been going pretty well for a good hundred years or so, so no one seemed too fussed with this system. For those not in the know, a clan was ruled or governed by one family, and from that family would be the chief of the clan. The extended family group that made up the clan mainly lived together in a way that we today would recognise as an agricultural town with joint-tenancy farms. The chief was the one who owned the land and he would lease that land to tenant farmers who then did their thing to work the land.

When looking at this system, the feudal influences are there and get even stronger when you find out that when the men of the clan pledged allegiance to the clan chief, they were also pledging military service. Which was often called upon in raids and plundering of neighbouring clans. As you can imagine there were several clan feuds, both big and small, wandering about.

If we leave the Scottish clans for a moment and have a look at who this Young Pretender is, we would find out that there is in fact two pretenders. We’ve already briefly met Charles Edward Stuart, but the one who went by ‘the Old Pretender’ is Charles’ father, James Edward Stuart. Way back during the years of the Glorious Revolution, so around 1688 and ’89, Charles’ grandfather, James VII and II had been deposed as the King. Leaving James and his son Charles without the cushiony chair they believed to be rightfully theirs.

Both the Pretenders seemed to not have the best of luck when it came to taking back their throne and history certainly tells us that it really didn’t end in the way they had hoped. Their only real supporters were the Scots, and it’s this popularity with the Scottish people, that they relied on a little too much. The Pretenders’ attempts at launching an uprising suffered from several big problems: poor organisation, bad timing and a whole lot of false hope.

Although the Battle of Culloden can be easily seen as the Scottish Highlanders against the English, it’s important to keep in mind that that isn’t what it was on the day. In reality, the battle was fought by those who supported the Pretender against those who weren’t really a fan of the Pretender. So much like politics today, it was common to have many families split down the middle, meeting each other in the middle of the battlefield.

There also seem to be two views as to the quality of the young Prince’s army. One is of primitive Highland clans who preferred using Guerrilla tactics, which would naturally come in handy when raiding neighbouring farms, and the other is of trained soldiers, drilled in the ways of French military tactics. As we know the victors get to tell the story, so it would make sense for the victorious English to make the Scottish supporters of the Young Pretender out to be heathens.

The sheer size of Charles’ army does seem to be a bit inconvenient in fighting a guerrilla war, and the idea that it was a ‘clan’ army is put aside when you see how many of the lowlanders supported Charles’ claim to the throne, there were even some English who had come to fight for the bloke. Some didn’t even care about Charles, they just weren’t happy with the 1707 Act of the Union, which joined England and Scotland to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

Events of Culloden

It was on 16 April 1746 at Drummossie Moor that the Jacobite army stood in what would become their last effort in retaking the British throne for the Stuart dynasty. The Jacobites fought for the Young Pretender, a Bonnie Prince Charlie, who had largely grown up in Italy, and George II, the sitting monarch sent his son the Duke of Cumberland who fought to stay on the throne.

On that fateful day, the battle would only last barely 40 minutes and would end in a horrendous defeat for the Jacobites. The size difference of the two armies probably had a lot to do with it. Charles had about 5000 men, which normally would be a fair number but when the other guy has 9000, 5000 starts to look a little small. It also didn’t help that the Jacobites weren’t in the best of health.

The Jacobites went into the battle with a sense of encouragement. They had done well at the Battle of Prestonpans not too long ago and thought they may be able to recreate the victory at Culloden. But unfortunately, twas not to be.

Now sources vary, but by the end of the battle, it’s claimed that around 1500 Jacobites were killed, while Cumberland’s Redcoats only lost around 50 to 100 men.

By spring of 1746, the Jacobite Rising was having some serious issues. They had started strong, had won at the Battle of Falkirk, but just couldn’t seem to carry the momentum. Instead of pushing on to London to take the throne, when they got to Derby word reached them that the Duke of Cumberland’s troops were on their way to take Inverness. And so Charles made the mistake of returning north in an attempt to prevent Inverness being taken for the other side.

The only issue with this was that the Jacobite’s were quite a fair way from Inverness, so the effort to rush back meant that the Prince’s men were bloody exhausted when they got there, and with food and money running out, it would take time to get everyone back up to full strength. Supposedly it was so bad that the Jacobite soldiers were on rations of only 3 biscuits a day. Bloody hell, you can’t do anything on 3 biscuits.

And so it was decided that rather than risk a proper battle with everyone so weak and tired, the Jacobites would launch a surprise night attack. Take Cumberland’s men while they were sleeping and make them rue the day they ever thought they could take Inverness. Now this would have been a brilliant plan had it worked. But alas, sometimes people who have only eaten a couple biscuits are just too slow when walking to attack a sleeping army, and soon the night was over and the sun was peaking over the horizon, forcing the night attackers to turn back.

But all was not lost. The Jacobites did have the chance to tactically retreat back to Inverness, gather some supplies, have a good meal and a decent sleep and take on the opposing side another day. And yet, to some this seemed like a stupid idea.

The Prince just wanted to go right then and there and fight, but his soldiers were not only weakened from their 3 biscuits, now they were exhausted after marching through the night, not to mention that not all the Jacobites had even arrived in the area yet. Senior commanders of the Pretender were pointing all this out, but the Prince was resolute. They would fight right here, on the moor at Culloden. What an idiot.

And so just past lunch, the Jacobites opened fire on the government soldiers, the government soldiers responded and the Battle of Culloden had begun.

By the time the Jacobites were given the order to move forward, the government troops were ready for the Highland charge. Even though the ground was boggy, many of the Jacobites reached the opposition’s frontline as the battle descended into hand-to-hand fighting. The King’s troops decided to try something new in the form of a tactic that had them bayoneting the exposed side of the bloke to the right, rather than the one directly in front of them, and it seemed to work for them because it wasn’t long before the Jacobites turned and fled.

But over the coming weeks, the worst was not over for the Jacobites, as many who had escaped the battlefield were hunted down and killed by Cumberland’s men.

Naturally Charles watched all of this from a position of relative safety. And as Prince Charles himself was hunted, he managed to escape, hiding around in Scotland for about five months before being able to escape to France disguised as a maid. Charles ended up living out his life in exile, drinking to excess in Rome until he finally died in 1789, ending the dream of a Stuart once again sitting on the British throne.

The aftermath

So even though the disastrous end for the Jacobites to the Battle of Culloden marked the end of their attempt to get a Stuart back on the throne, it actually wasn’t the end.

In the weeks and months that followed that fateful day, about 1000 extra Highlanders who fought for the Prince were hunted down and killed. And Cumberland’s dragoons, tasked with not taking any prisoners, turned out to pretty ruthless. Some of the Jacobites headed towards Inverness, some headed into the mountains, but in the end the troops were pretty thorough, even going so far as to burn highland homes even if they hadn’t had anything to do with the Jacobites. There really wasn’t any asking about anyone’s involvement.

As a warning to future uprisings, the British Government were determined to destroy the highland way of life, and that meant forbidding any wearing of highland dress, highlanders weren’t allowed to carry weapons of any kind, and the clan system wasn’t looked upon favourably.

Not all Highlanders that were hunted down were killed though. What may have seemed like luck at first, quickly turned into despair, when those who were taken prisoner, about 3500, were either executed, sent to a prison to die or transported to the colonies, effectively being exiled.

But the public weren’t behind Cumberland and his ruthlessness. Soon the public opinion turned and Cumberland was nicknamed ‘the Butcher’ for the way his men hunted down and slaughtered fleeing Jacobites.

Here’s historian David Nash Fords telling us exactly what Cumberland’s orders were:

After the battle on April 16th, 1746, Cumberland gave orders for the systematic extirpation of all ‘rebels’ who were found concealed in the Highlands. All houses where they could find shelter were to be burnt and all cattle driven off. This was interpreted to mean the killing or burning of all Highlanders found wounded or with arms in their hands, and Cumberland did nothing to soften such an interpretation of his orders. Hence came his well-known sobriquet of the ‘Butcher’, which was given to him in London as early as August of that year.

So the people turned on Cumberland fairly quickly. Which makes sense, especially since in this process of killing and burning whole Highland clans were killed off or forced to flee the land that their family had been working probably for centuries. A story we’ve heard countless times through history and one that is still repeated in the present day.

After the brutal slaughter of highlanders by Cumberland, the deterioration of highlander life only accelerated further. The government imposed pretty strict and restrictive laws on clan chiefs and pretty much on all aspects of Gaelic culture. So that meant no clan tartans, or really any plaid design, and no bagpipe music. Really anything that could be seen as culturally Scottish needed to go.

And then of course, the bits of land in the highlands that now stood vacant after the slaughter of their owners, were given to outsiders, usually lowlanders loyal to the British government.

And yet again, we see the victors being the writers of the history. All the wording gives us this impression of ‘kilted primitives’, heathens that were bent on ruining the idea of a ‘single centralised Britain’. But I suppose if we were to stop and think about this for a moment. If the people up north were really disorganised heathens, then they would be no match for a well-trained and oiled army. So by insisting on the language choice the British are kind of showing their hand there.

But it did seem like the Battle of Culloden was the catalyst for this ‘kilted primitive’ narrative that went around. And the effects of this narrative and everything that came after the Battle were pretty far reaching as we already know with the banning of tartans, bagpipes, speaking the Gaelic language, carrying any sort of weapon, really anything that signified Gaelic culture was out. Which is so sad and disappointing, not only for those living through it, but for us here in the future, so many things were lost forever in the ban, bagpipe tunes that had been passed down by ear for centuries, plaid designs that were taught by eye, stories of origin that were told to the children.

And then we get to the Highland Clearances, where inhabitants of land in the highlands are forced to vacate their home and lands, so that livestock could be brought in. This began in the mid-to-late 18th century, so around the time of Culloden, and continued on and off well into the 19th century. And this removal really put a stop to the clan system with many leaving Scotland for good. And that’s why you’ll find so many people of Scottish descent scattered throughout the world.

Visiting Culloden today

Today the Culloden Battlefield is a memorial to those who lost their lives on that day and the days and weeks that followed. And it’s open to any who would like to visit. You can walk along the battle lines marked out by flags, see the clan markers and visit the memorial cairn built in the centre of the battlefield.

The markers weren’t put in until 1881, a good 130 years after the battle. It probably wasn’t a good idea to do anything clan related before then. Upon the stone markers are the names of clans that are known to have fought at Culloden. So a lovely way to honour their contribution to something that they believed in, even if it didn’t exactly work out.

The memorial cairn that you see was also added in 1881, by a one Duncan Forbes. Forbes was the owner of Culloden House that gave the site its name. What’s really interesting about the cairn is that geophysical tests undertaken in the immediate area recently does show the presence of mass graves. So it seems well-placed.

A lot of those who visit Culloden do so because they’re interested in their own ancestral part. And there are plenty of resources to find out if the clan you belong to had a hand in the events of the day. Make sure to check out the ancestry hub, where you can discover the origins of your name.

Because there was really no official clan tartan back in 1746, it was pretty hard to identify which clan the fallen fellas belonged. So many were identified through either their cap badge or clan plant they may have worn, which were often local to the area their clan held. So rather than being grave markers, the clan markers are more symbolic markers for those clans known to have fought and lost at Culloden.

Even though we have evidence of mass graves around the memorial cairn for the Jacobites, the graves of those who died fighting for the government is still unknown to us.

Something that has come against some controversy is the stone known as the ‘Field of the English’. It’s a stone that sits behind the Government troop front line and is meant to mark the mass grave of those who died fighting for the Government. But there is no evidence that there is a grave in that spot at all. Not to mention the inaccuracy of the stone name. As we already known the government side wasn’t made up of just English soldiers, it was supported and fought by anyone who opposed the returning of a Stuart king, and that included those from all over.

The battlefield has been carefully cared for by the National Trust for Scotland. And even though a road was put in that basically cut straight through the battlefield in 1835, since the 1930s the National Trust has made considerable efforts to restore the site to how it would have been to those who fought for who they believed to be the rightful king on that fateful day.

Thanks to this restoration, as a visitor you can really get a good sense of just how boggy and uneven the ground was. You can even pick up a hand-held guide from the visitor centre that through GPS can tell you what took place in what park of the battlefield.

If you’re visiting Culloden, then you really cannot go past the Culloden Visitor Centre. It sits right next to the battlefield and you’ll find all sorts of artefacts left behind by fallen soldiers, not to mention the interactive displays.

The 360 degree battle immersion theatre really puts you right in the middle of the battle. It tells the story of the events that led up to the battle and then shows you how the battle played out all around you. Sounds pretty immersive to me.

The Culloden Visitor Centre also boasts an accredited museum, where you can see the lead up and aftereffects from both the perspective of a Jacobite and a Government soldier, which will show the interesting aspects of the two stories. Not to mention the 200 exhibits on display, which does include a pretty awesome Brodie sword, which has some pretty cool imagery of a Medusa and dolphins on its hilt, as well as a rare find, a blunderbuss, a type of short firearm dropped by a government soldier.

In fact the archaeological finds that have come from the battlefield have allowed for more clarity on the events of the day and provided more detail on the battle itself. You’ll be able to see artefacts like musket balls, buckles and Jacobite crosses as you wander the exhibits of the visitor centre.

It actually wasn’t that long ago that the original visitor centre had to be moved to its current position, as research showed that it was sitting right where part of the government army had fought, so in the interest of restoring the area to how it was in the 18th century it was probably best that it was moved a little bit more out of the way.

While you’re in the area, make sure you stop by Leanach Cottage. The cottage is a beautifully restored thatched roof house, which is believed to have been built in the early 18th century and is an example of the kind of building that would have been around at the time of the Battle of Culloden.

Sitting pretty much in the middle of the battlefield, it’s a wonder the place is still standing after so many years. And you could even call it the first Culloden Visitor Centre, the family that inhabited and lived in the cottage until 1912 were known to give tours of the Culloden Battlefield. Falling into disrepair after the family left, the cottage was recently restored and was reopened to visitors in 2019.

And of course as at any tourist location, we can’t forget to visit the museum shop, where you yourself could pick up a keepsake or even try some of that Culloden whisky.

-

The Jacobites who turned slave owners after Culloden - The Scotsman

New even putting visitors centre stage at bloody Battle of Culloden - The Herald

Battle of Culloden is being fought anew … against an army of house developers - The Guardian

A tourist’s guide to Culloden Battlefield: things to see and do - Daily Record

The story behind the Culloden battlefield and its links to slavery - The National

Battle of Culloden site saved from plans for holiday village by ministers - The National

New podcast delves into the history of the Battle of Culloden - Ross-shire Journal

-

Battle of Culloden - Britannica

The Battle of Culloden - National Trust for Scotland

Museum - National Trust for Scotland

Leanach Cottage - National Trust for Scotland

Your guide to the Battle of Culloden - History Extra

The Two Pretenders - Historic UK

Culloden Battlefield - Visit Scotland

1746: Battle of Culloden - ScotClans

Grave markers at Culloden - Culloden Battlefield

After Culloden: from rebels to Redcoasts - Military History

Leanach Cottage - Culloden Battlefield

Culloden - National Trust for Scotland

Battlefield - National Trust for Scotland

Clans - National Trust for Scotland

Culloden: Why truth about battle for Britain lay hidden for three centuries - The Conversation

The Battle of Culloden - Historic UK

The Battle of Culloden - Wilderness Scotland

Battle of Culloden - National Army Museum

Battle of Culloden - New World Encyclopedia

The Battle of Culloden - Scottish Tartans Authority

Outlander ‘hotspot’ at Culloden Battlefield cordoned off - BBC News

Disclosure: As an affiliate marketer, we may receive a commission on products that you purchase through clicking on links within this website.