South Pole

Let’s head on down as far south as we can go to see just what’s going on down there

Who were the first people were to reach this mysterious spot and can you visit it yourself today?

Antarctica

Right on the bottom of the planet, at the southernmost point, you can find the south pole. Conveniently located in Antarctica.

Thanks to the massive ice sheet that sits on the land of Antarctica, at about 2700 metres thick, this means that the South Pole is up pretty bloody high, making it a little chilly. At least compared to the North Pole, which sits at sea level because it’s in the middle of the Artic Ocean. What a weird place to have a pole.

Now the south pole is fairly singular in that it has no native plants or animal life, but there are parts of the Antarctic continent that do have some native flora, like moss or lichen, and then there are some mites that like it mighty cold.

Antarctica itself has quite the story of discovery. Before anyone knew it existed, explorers were sure that there was some kind of landmass to the south just waiting to be discovered.

The Ancient Greeks love things to be symmetrical, and since there was so much known land in the Northern Hemisphere, with Europe and Russia and China, their thinking was that there must be something equally as big to the south, otherwise the Earth would be all lopsided. They called this ‘Unknown Southern Land’ Terra Australia Incognita.

Because this mythical place was incognita for so long, Greek and Roman philosophers needed something to call it. Because they knew that the Great Bear constellation of ‘Arktos’ was located above the North Pole, they imagined that this to-be-discovered piece of land would fit the name of ‘Antarktikos’, or ‘opposite the bear’. And so it did.

Like many of the ‘discoveries’ by Europeans, the native inhabitants who lived in the local area, knew of a frozen landmass many a century before Europeans even bothered to come around.

Now of course, Antarctica doesn’t have any native inhabitants, but those islands not too far to the north did.

For example, there’s an oral tradition out of Rarotonga, the largest of the Cook Islands, that tells of Ui-te-Rangiora, a Polynesian navigator, who discovered a great frozen region after sailing south of New Zealand all the way back in 650 AD.

It wasn’t until the 16th century that Europeans even came close to catching a glimpse of Antarctica. The first to attempt it was the explorer Ferdinand Magellan when he rounded the southern tip of South America in 1520 while sailing around the world.

Then it’s not until James Cook, who claimed Australia for the British, decided to explore the southern waters in the 18th century, that we start to get an idea of just how far south this mystery land really is.

After coming up against pack ice that drove him north each time he tried, Cook decided that perhaps this landmass wasn’t really all that worth looking into. Even though Cook never actually saw what we know today to be Antarctica, there were many a sealer and whaler that did. Unfortunately these guys were more interested in the seals and whales and weren’t exactly open about what was down this part of the earth, in an attempt to protect their favourite fishing spots.

Antarctica, the landmass, wasn’t even first seen with western eyes until 1820. But exactly as to who saw land first has been debated. During a Russian expedition down to the Antarctic, Thaddeus von Bellingshausen said that he saw

an ice shore of extreme height.

Unfortunately, it was around the same time, that Edward Bransfield, a Royal Navy Officer on a British mapping expedition reported that he saw

high mountains, covered with snow.

At least they both saw the same thing.

For a while small discoveries were common, but it wasn’t until we get close to the turn of the century that the real advances in geographic and scientific knowledge were made. The number of expeditions setting out to explore this vast landmass grew in number, and with each came new technologies of surviving the harsh weather. Even today there is a very lively scientific community living in Antarctica, and tourists can even drop by for a visit. More on that in a little bit.

Antarctica is quite singular in that it has no political boundaries. Even though many nations have claimed Antarctica for themselves, these are largely ignored. You could say Antarctica is the last continent free of politics. That doesn’t sound too bad actually.

So when Antarctica was first seen to be real, several nations thought they’d jump quick smart onto claiming the land for themselves. These included Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Obviously things weren’t exactly civil, each saying they were the rightful owner of Antarctica for whatever reason.

But then, something pretty crazy happened. Instead of fighting over the land, those who held territorial claims over Antarctica got together and signed the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, which said that Antarctica should be a place for peaceful scientific research only. No military and no mining. What alternate universe did this happen in? Cause it certainly isn’t the one I live in.

All up 12 countries originally signed the International Treaty of 1959: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, (what was at the time) the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States. This Treaty declared that forevermore Antarctica would be

A natural reserve, devoted to peace and science.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Since the signing, another 41 countries have added their signatures to the Treaty, and everyone comes together in annual meetings to make group decisions on how Antarctica should be managed, while always keeping to the original Treaty of Antarctica remaining neutral and peaceful.

Under the Antarctic Treaty, no country owns any part of Antarctica, we’re all just visitors who love a bit of science. There are super strict rules around using Antarctica, especially around exploiting the continents resources, including commercial fishing, sealing and mining.

If you want to hear a bit more about this fascinating piece of paper then check out the I Digress episode on the Antarctic Treaty.

The different poles

The South Pole can be a tricky one to wrap your head around. Because technically, when you’re standing at the South Pole no matter which direction you face, you’re always facing north.

Time is also tough to figure out. Because all lines of longitude meet at the south pole, it means that the sun is only directly overhead twice a year, so at the equinoxes. Which means that if you were to lie down over the exact spot of the south pole for a whole day, you could revolve around every single time zone.

And to make things super uncomplicated, the scientists and explorers living and working at the south pole decided the best thing to do would be to use whichever time zone they feel like. Because all the time zones come together at the pole, the time can be whatever you want it to be.

The South Pole itself is the southernmost tip of Earth. But thanks to moving continents and plate tectonics, where that point is, is constantly moving, by about 10 metres per year.

But which South Pole are we referring to? Cause there’s a couple of different ones.

The Geographic South Pole, or the Terrestrial South Pole, is exactly at 90 degrees latitude South. If you drew a line between this pole and the Geographic North Pole, that line would be where the Earth’s surface intersects with the Earth’s axis of rotation. So it’s the line that the Earth turns on. You can see this pole near the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, and you’ll know you have the right one because it’s marked with a silver rod topped with bronze.

Our next pole is the Magnetic South Pole, and this pole is the one you refer to when you use a compass. This is thanks to the Earth’s magnetic field. This pole also moves though, roughly 13 km in the northwest direction every year due to changes in Earth’s magnetic field, and can be found on the Adélie Coast.

Out third pole is the tourist’s favourite. The Ceremonial Pole is marked by a red and white stripped pole with a mirrored ball on top. And this pole doesn’t really move. You’ll know you have the right pole because there will be 12 flags surrounding it, one flag for each of the original countries to sign the Antarctic Treaty. Located near the Amundsen-Scott South Pole, it’s a brilliant spot for tourists to stop by.

The race to the South Pole

Once Antarctica had been spotted and it was confirmed that there was in fact a landmass at the bottom of the world. Explorers naturally decided they wanted to be the first one to reach the South Pole.

Technically, the South Pole is a lot easier to travel to than the North Pole, mainly because the South Pole can be found on land, whereas the North Pole is in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. But as we will soon find out, reaching the South Pole wasn’t exactly a walk in the frozen park.

And it’s the ‘Race to the Pole’, that took place in the early 20th century, where all the excitement about exploring Antarctica resides.

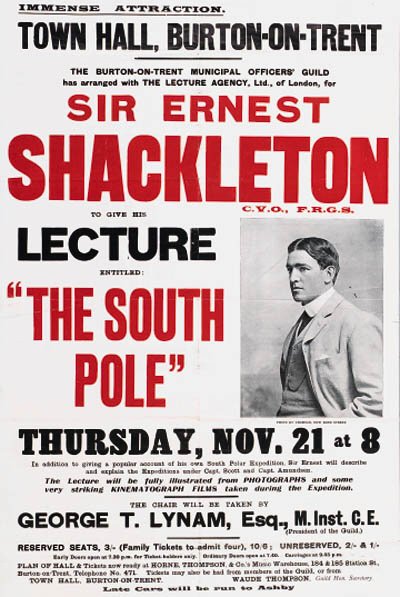

The first to attempt it were a group of European and American explorers, made up of British Captain Robert Scott, and Antarctic explorers Ernest Shackleton and Edward Wilson, whose 1904 expedition came within 660km of the pole before being forced to turn back thanks to bad weather and not enough supplies.

Clearly exploring this barren land wasn’t for the faint of heart, as when the group returned to their base, they were described as

Almost unrecognisable [with] long beards, hair dirty, swollen lips and peeled complexions and blood-shot eyes.

Despite this, Shackleton and Scott were determined not to give up.

Shackleton actually came within 160km of the pole in a 1907 expedition, he was getting closer, but unfortunately had to turn back again, thanks to bad weather. And it’s a good thing they did, because this retreat was pretty harrowing, almost costing the expedition their lives. Thankfully they made it back relatively unscathed.

But as exciting as Shackleton’s attempts were, it’s the race between British Captain Robert Scott, and Norwegian Captain Roald Amundsen, where the excitement really is.

In 1910 and 1911 the pair brought southern polar exploration to its head, and it couldn’t have been more perilous, with several lives being lost along the way.

1910 was going to be Scott’s year, he was determined to make it this time round. Leaving Cardiff for the South Pole upon his ship, Terra Nova, Scott had the provisions and scientific equipment to get him to the pole and back, as well as trusted sailors and scientists making up his team.

But it was at his last stop to fuel up with last minute supplies in Australia that Scott got the most interesting telegram from rival Roald Amundsen.

The telegram read:

Beg leave to inform you Fram [that’s Amundsen’s Ship] proceeding Antarctica.

Amundsen appeared to be heading for the pole as well. Shockingly he had kept his preparation for his South Pole expedition top secret, and now found himself just ahead of Scott on his journey south.

What’s really odd about Amundsen’s preparation, was that initially he had been vying to be the first person to reach the North Pole, but when he heard that the American duo of Frederick Cook and Robert Peary had already ticked that accomplishment, Amundsen quickly adapted his plan, in the complete opposite direction it would seem.

Now Amundsen made organisation his top priority, and that meant being meticulous about his planning for the expedition south. He went and sought the expertise of those who live and work in the kind of conditions he expected to experience when attempting to walk to the South Pole. And so he used the skills he learnt, like driving dogs and building igloos, to make his journey that bit easier.

Here's Amundsen’s take on preparation in his memoir, My Life as an Explorer:

Victory awaits those who have everything in order – people call that luck. Defeat is certain for those who have forgotten to take the necessary precautions in time – that is called bad luck.

He’s not wrong there.

It’s at this point of January 1911, in the middle of summer, that both the Terra Nova and the Fram arrived in Antarctica.

Both teams camped out here for the Antarctic winter, with Amundsen’s camp over at the Bay of Whales, and Scott’s at McMurdo Sound, some 640km away from each other.

It wasn’t until 18 October 1911 that Amundsen’s expedition set off for their attempt at reaching the South Pole. Interestingly Scott held back, beginning his trek three weeks later at the start of November.

Now Scott stuck to the tried-and-true route taken by Shackleton many years before, and while this may have been a logical way forward, his travel wasn’t necessarily so. The ponies and motorised equipment he brought down with him either died or broke down, unable to cope with the extreme temperatures.

Meanwhile, travelling by dogsled, Amundsen forged a new route, that with his team of highly experienced skiers, explorers and mushers, thought would pay off. And they were right, with Amundsen reportedly reaching the South Pole in December.

He and the team hung around for a couple of days taking scientific observations of the site, and leaving behind messages and any equipment they could spare for Scott and the few men who hadn’t yet turned back.

Arriving back at their base camp on 26 January, and having essentially walked more than 2500 km, the round trip had taken Amundsen and his expedition 99 days. Not a bad effort at all.

Unfortunately, Scott would reach the South Pole just 33 days after Amundsen. Met with the sight of Amundsen’s camp left set up for Scott, the bloke was understandably heart broken.

Here’s a little something he wrote in his diary of the accomplishment:

Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here, and the wind may be our friend tomorrow. Now for the run home and a desperate struggle. I wonder if we can do it.

And a struggle it would be for the men of Scott’s team. None of them would make it out alive.

On their return journey, Scott’s team faced much harsher weather than Amundsen’s had seen. The temperature was colder, the wind harsher. They’re supplies were dwindling fast, and so too their lives.

Suffering from hypothermia and frostbite, the first member of Scott’s team, Petty Officer Edgard Evans, died in his tent on 17 February 1912.

Here’s the short note in Scott’s diary:

In case of Edgar Evans… He died a natural death…

Though not a very warm one.

The next to lose their life was Captain Lawrence Oates. Though the date could be either the 16th or the 17th of March, as Scott was struggling to keep track of the days in his diary. It seemed that Oates was ready to go, here’s what Scott wrote:

It was blowing a blizzard. He said, ‘I am just going outside and may be some time’. He went out into the blizzard and we have not seen him since… We knew that poor Oates was walking to his death, but though we tried to dissuade him, we knew it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman. We all hope to meet the end with a similar spirit, and assuredly the end is not far.

Scott couldn’t have been nearer the truth.

Less than 18 km away from their final supply depot, it was ridiculously bad weather that prevented them from making it home.

Weak from exhaustion and extreme hunger, Scott wrote his last diary entry on 29thMarch 1912. Here’s what he said:

…Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have tried the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but surely, surely, a great rich country like ours will see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for…

The bodies of Scott, and two other team members, Wilson and Bowers were found in their tent by a search party seven months later on 12 November 1912. The bodies of Oates and Evans have never been recovered.

Scott’s diary entries are absolutely fascinating and if you’re interested I encourage you to check them out. Although beware, they can be tough reading.

In the months following, Amundsen was celebrated as a great explorer the world over. Getting personal telegrams of congratulations from Theodore Roosevelt, US president at the time, and George V, the British Monarch at the time.

And Scott’s achievement didn’t go unnoticed, posthumously receiving a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath.

Now it wasn’t until 30 years later that the appropriately named Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station was established and is still in use today. But the next overland expedition to the South Pole didn’t take place until 1958, over 40 years after Amundsen and Scott had made their mark.

And this time it would be New Zealand’s Sir Edmund Hillary, whose fame preceded him after being the first person to make it to Mount Everest’s peak in 1953. Hillary’s expedition would be just the third to reach the treacherous South Pole, and interestingly the first to do so in vehicles.

And then of course, as technology gets better, the first tourists were flown to the South Pole in 1987.

Living at the South Pole

For scientists today, who live at the South Pole, it’s a little bit of a different day to day experience than what you or I might have at home.

So thanks to being at the bottom of world, there are actually only two sunsets and sunrises each year. Which means for half of the year, they are in the dark, and for the other half, they can see the sun.

The majority of people visiting and working in Antarctica will be there during the summer months, as the weather is generally kinder. And throughout the winter months, the number of people calling the South Pole home dwindles to about 50. That’s not very many at all.

Different countries have a preferred Station that they will send their scientists to. And of course, thanks to the Antarctic Treaty, science is why people head down to the South Pole in the first place.

According to the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs in 2009 almost 30 countries were operating over 80 research stations all for the glory of scientific advancement.

The Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, named after the famous explorers, was set up in 1956 and has been run by the United States ever since. The place is huge and can house anywhere from 50 to 200 scientists and support staff at any one time.

What’s pretty cool about the Amundsen-Scott Station is that it isn’t actually built on the ground. Its height can be changed to stop it being buried by snow from storms, which can accumulate pretty bloody quickly. And thanks to the ever-freezing temperatures, the stuff doesn’t melt, so the station itself has to have the ability to rise above.

This Station has pretty much everything to be completely self-sufficient, which it has to be in Winter. Thanks to ridiculously cold temperatures and those damn gale-force winds, you’re pretty much on your own. So you have to be prepared. And that means, all your food, medical supplies, fuel, everything needs to be with you and ready to sustain you through the long and cold winter months.

Because science is the name of the game in Antarctica, there have been some pretty great discoveries coming out of the frozen wasteland. Early on, observations out of the research stations helped to support the theory of continental drift. Basically rock samples collected nearby the South Pole, showed that at some point in the past they had sat at tropical latitudes. I reckon they definitely miss that beach-side weather.

And don’t even get me started on the South Pole Telescope checking out cosmic microwaves and radio waves.

Tourism at the Pole

If you’re sweating out of your eyeballs in the height of summer, and are thinking that it probably would be lovely idea to pop on down to the coldest place on earth just for some relief, well you’re in luck. Tourism is growing yearly for visits to Antarctica.

Obviously the main goal is of course science. But there are more and more cruise ships making stops nearby so that paying customers can have an out of this world experience.

In 2007, 46 000 tourists stopped by for a visit. Now that is quite a number, and it had to brought down, for fear of disrupting wildlife and just the larger environmental impact. So by 2011, not quite 20 000 tourists were allowed to visit the Antarctic Peninsula, a much more manageable number.

If you are one of the lucky ones to score approval to visit this icy wonderland you can climb some frozen mountains, can dance with some emperor penguins, go hiking, it’s all doable, and there are many adventure companies who will sort out all the details for you.

But of course, reaching the ultimate grail of the South Pole has to be at the top of your list of things to do while in Antarctica. And you can visit both the ceremonial and geographical poles in several different ways; you can walk over, ski over, drive over, or fly over, it really seems to be up to you, and probably your budget.

And once you find yourself at the Ceremonial South Pole, it’s already Insta worthy, with the flags of the original signatories of the Antarctic Treaty surrounding it, for the perfect photo.

-

How to cruise Antarctica in just one week - The Australian

Inside a failed polar expedition - Outdoors

‘Polar Preet’ fastest woman to ski to the South Pole - Snow-forecast

Why there’s a bust of Vladimir Lenin in the most remote place on earth - 9 News

Lost history of Antarctica revealed in octopus DNA - Science

-

South Pole - National Geographic

The South Pole - Cool Antarctica

Antarctic Interior and South Pole Expeditions - Swoop Antarctica

10 fun facts about Antarctica - Aurora Expeditions

50 amazing facts about Antarctica - LiveScience

The race to the South Pole: Scott and Amundsen - Royal Museums Greenwich

Roald Amundsen: Polar Explorer - Royal Museums Greenwich

Exploring Antarctica: a timeline - Royal Museums Greenwich

Shackleton’s search for the South Pole - Royal Museums Greenwich

South Pole exploration: Robert Falcon Scott, 1901-04 - Royal Museums Greenwich

Reaching the South Pole during the Heroic Age of Exploration - Library of Congress

History of Antarctic - Britannica

8 famous Antarctic expeditions - LiveScience

Scott’s diaries - Scott Polar Research Institute

Antarctic Exploration - American Museum of Natural History

Science in Antarctica - Discovering Antarctica

Poles and directions - Australian Antarctic Program

Wandering of the Geomagnetic Poles - National Centres for Environmental Information

Disclosure: As an affiliate marketer, we may receive a commission on products that you purchase through clicking on links within this website.